- Home

- Betty Halbreich

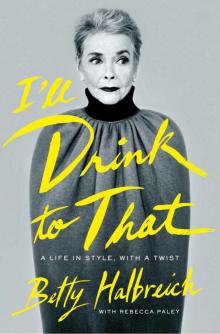

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist Page 11

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist Read online

Page 11

It was hard to have Mother, with whom I had become even more emotionally entwined after my father’s death, witness my debilitated state in the hospital. But I experienced a wholly different kind of suffering as I watched my children—Kathy, a high-cheekboned, determined, and leggy twenty, and John, a wild-haired and gangly eighteen—laugh all the way up the same walkway Sonny and my mother had traveled to see me.

How dare they.

Visiting their mother in a mental institution should have been a more serious affair. Was this how much they cared? Maybe so.

Again I was brought into a room of clinicians. This time, however, I sat on a stool as if their plan were to rotate the specimen.

The doctors questioned my children on their feelings about their mother, and the answers were so brutal that I’ve pushed them out of my head. The pediatrician had been wrong; it was not enough to bundle them up and open the window. When I hurt myself in a pathetic attempt to gain Sonny’s pity, I hadn’t given them a passing thought. What kind of mother doesn’t take into account her children’s well-being in all moments? Apparently, everyone was agreed, not a very good one. But all I wanted was a life and some happiness. Now that my children were young adults, didn’t I deserve as much?

I didn’t allow the dynamic between my children and me to be altered by our awful session. (I don’t like confrontation, and, clearly, neither did my children, because no one ever brought it up again.) But after six weeks in the hospital, I didn’t feel any better than when I’d entered. I was no closer to keeping my dining-room table and breakfront together. Indeed, when a doctor announced I could go home—that very day!—I responded that I couldn’t possibly. “I’m not ready.”

Even my release from a locked mental institution had to be carried out my way.

The doctor assured me that I was ready and was indeed going home, so I asked to make a phone call, which I placed to Sonny.

“Could someone come pick me up?” I asked. “I’m being released.”

A few hours later, I walked out of Payne Whitney, my suitcase and pillow under my arm, and the name of a psychologist to call in my purse, and I found Prince (already wearing his summer uniform of light gray jacket, pants, and matching chauffeur’s cap) waiting for me with the car. He was alone.

I arrived home to find that in my absence Max the dog, who’d been suffering from cataracts, had gone completely blind; my sister-in-law, separated from her husband, had moved in, taking the varnish off my dresser with her spilled perfume and putting up pictures of her friends in my bedroom; and Sonny had found an apartment with a woman friend.

Not a day later, Prince was back. After being alerted to his arrival from my doorman, I went down to the lobby to find out the reason for the surprise visit. Silently Prince opened up the back door of the car. There sat a large broken box I recognized instantly. How could I not? My wedding dress was hanging out of it. Right after my wedding, I had given my mother-in-law my bridal gown to house in one of her many large closets, and twenty years later she’d sent the chauffeur to return it.

CHAPTER

* * *

* * *

Five

I awoke in the dark of early morning to the swimming sensation of sleeping alone. Sonny’s presence lingered all around the bedroom, from the still-too-big bed to the tidy, washable liners he had made to cover the entire length and width of my dresser drawers to the checked gingham fabric from his family’s company in which I’d cocooned the walls.

I searched for relief in housekeeping, making the bed just as soon as my feet hit the floor. Well, at least no one would jostle the straightened mattress, loosen the tight hospital corners, wrinkle the flawless bedspread, or flatten my plumped pillows, I reassured myself.

However, this morning I suffered from a particularly bad case of my chronic school stomachs. It was my first day of work at Bergdorf Goodman.

I opened my closets, where organization offered another moment of relief. How I’d lovingly tended to them when Sonny and I had first moved into the apartment on Park Avenue. There were storage boxes devoted to their accessories with quilted liners and hangers for all eventualities—even ones on which to hang fur stoles. I’d had the heavy wooden coat hangers monogrammed and those for delicates wrapped in cloth.

Without thought I chose a bottle green jersey Cacharel suit and a blouse in a red-and-yellow paisley pattern. Then I turned to the best part of my closets—the custom-built shoe racks. Running along the inside length of the doors, they occupied otherwise useless space and were much more visible than if my shoes were on the floor. Their ingenuity made me proud. From the slanted poles, each of which held a shoe, I chose a pair of neutral suede pumps that I imagined would be comfortable for a salesperson on her feet all day.

I moved on to the dresser, arranged as diligently, if not more so, as one in any store. The bottom drawer housed my alligator, cocktail, and beaded evening purses in individual Mark Cross cotton dust-bag covers—all beautiful but too small for a single woman, someone who needed to carry credit cards, money, makeup, and hairbrush when she went out.

In the middle drawer, my stockings were rolled into tight doughnuts (my own invention for keeping hosiery from its wish to be unruly), my underwear was hand-pressed, my nightgowns tied together with grosgrain ribbon in stacks, in the grand tradition of Isabelle the laundress. Although it was 1976, we female employees were expected to keep our legs covered, so I chose a pair of pantyhose.

Lastly I visited the top drawer, where my jewelry collection lived. Individual velvet bags opened up like little nests for my costume necklaces. Some pieces were in their original boxes, like a leopard pin that had once belonged to my mother. (I even had the card that went with it, addressed to her!) There was also an old jewelry box given to me by my mother-in-law, who’d had it monogrammed “B.H.” instead of the “B.S.H.” as was proper. From there I plucked a coral flower pin and the gold earrings my mother’s friend had given me upon my engagement.

My state of anxiety didn’t factor into my getting dressed. That aspect of my life was easy, in part due to my obsessive fastidiousness about putting things back in the right place. Even if I were Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? drunk, I’d still put my clothes and jewelry away with military precision before getting into bed, primarily because I found sleep impossible knowing that a single article I’d worn was out of place.

I didn’t need to stand in front of the mirror; I knew my look. Its straight, clean lines spoke of an aversion to frivolity that succumbed only to a love of great accessories. Eclectic jewelry—chunky turquoise bracelets and larger rings, or my beloved plastic cat pin from Henri Bendel—was the signature on an otherwise understated template. My short hair and simple makeup were practical though proud.

Pulling on my clothes was no more a problem in this moment, as I tried to move forward with my life and start a new job, than it had been while I was hiding out from it at Payne Whitney six months earlier. The other patients in the hospital had been so impressed by my put-together appearance. If only they had seen how I’d fallen apart once I left.

When I returned home from the institution, there were no children or husband to direct me. I ruminated on why everyone—except for Frieda—had fled. Was it selfishness, the only child syndrome, overindulgent parents, a new environment, or all of the above? I went over the equation again and again in my cavernous apartment and always came up with the same answer: I was to blame for the failure of a marriage and a broken family.

The loneliness almost put me back in the hospital. I terrified poor Frieda, who arrived one morning to find me on the floor, crawling, screaming, and crying. She tried to no avail to get me to eat something as I got thinner and thinner. My sister-in-law was good to me; she came around regularly to take me out for walks. Making our way down the avenue we were quite a pair, the glamour girl and the skeleton.

I was beyond lonely, beyond desperate. If there was a word

for my state, I didn’t know it.

Upon my discharge from the hospital, I’d been given a referral to a psychologist and a bottle of pills, which I immediately flushed down the toilet when I got home. It was a stupidly dangerous thing to do, but I felt extremely threatened by the medication. I did, however, call upon the psychologist.

My first visit to Philip was not without its fair share of apprehension. We met on the ground floor of the brownstone on Eighty-fourth Street, although his office was on the third, because the building’s service workers were on strike. As soon as I saw him—this tall, very, very thin, and definitely younger-than-I human being with long hair pulled back in a ponytail, I thought this was not going to be for me.

But he was the one to whom I’d been sent, and, like the Good Child, I always went where sent. Nursemaids, bedtimes, doctors, even husbands and a new home and city—I never questioned.

So Philip and I entered a tiny elevator that would have made even the most psychologically healthy person claustrophobic. (I wanted to rip off my spring cloth coat and head for the hills.) He closed the grate and, acting as operator-therapist, pushed down the lever. As the elevator shuddered terribly, Philip gave an apologetic smile. I will kill myself before this elevator kills me, I decided.

We made it to the third floor and entered his office, which had the coziness of a little living room with two good chairs, a couch, and a table with a lamp. More important, though, it was immaculate. I relaxed a bit.

Lying on the couch with Philip in a chair behind me so that I couldn’t see him, à la the Freudian method in which he’d been trained, I noticed an avocado tree he was trying to sprout from a pit. Things that bloom talk to me. That’s never going to make it, I thought, but kept it to myself. Instead I started in on the husband who wasn’t my husband, the children who weren’t children anymore, my apartment that wasn’t a home.

Coming out of that institution was like coming out of a movie house in the daytime. Everything was very light and glary for a good while, disorienting me even when I traveled home to Chicago, where I ran into a friend from New York who was having lunch with the new executives from Bergdorf Goodman. I was lunching with my mother at the restaurant in the famous Drake Hotel.

I’d first met Corinne Coombe, a tiny, attractive, Chinese American buyer, when I was at Chester Weinberg and she at Liberty House, a chain of department stores throughout Hawaii. She had gone to work alongside her best friend, Dawn Mello, at B. Altman under one of the last of the great retailers, Ira Neimark. When Mr. Neimark became CEO of Bergdorf, charged with bringing fresh air into the conservative store, he brought along Dawn as fashion director and Corinne as general merchandise manager. The three of them, on a trip to Chicago to scout locations for another Bergdorf that never came to be, passed our table on their way out. Corinne, delighted to see me, kindly introduced me to the group.

Corinne, a very spiritual person, had shown me a lot of kindness since my return from the hospital. Just across the street from me on Park Avenue, she and her husband took me under their wing. They checked in all the time and helped me to see a light at the end of the tunnel. In addition to making me dinner, Corinne insisted I come to work at Bergdorf. “After we left you that day you were having lunch with your mother, Mr. Neimark told me to ‘get that girl to come to BG,’” she said.

“In fashion, misery is often confused with style,” I said.

“Come and work at the store,” Corinne said.

“Nobody’s going to want me. I’ve been in a psychiatric institution.”

Although I was still in the middle of getting myself together, for some reason Corinne thought I could be helpful and insisted I call Bergdorf’s executive vice president, Leonard Hankin. With all my frailties, neuroses, and lack of experience, it was curious that jobs always found me. I never had to look for work or even make a résumé for that matter. My appearance, the way I paired a print or tied a blouse, gave the illusion of confidence and mastery. As frightened as I was, I heeded her counsel, made an appointment, suffered my standard stomachaches, dressed with care, put on the jewelry I’m known for, and met Mr. Hankin, a lovely gentleman from the old school. (Even with severe anxiety, another side of me pulls it together and says, You have to. Let’s go!) He ran the fur department and other divisions I was too anxious to ask about. All I remember before I went blank was his asking, “What are we going to do with you if you come to BG?”

Corinne must have done quite a job lobbying because the store decided to take a chance on a tongue-tied woman straight out of an asylum.

And so, another round of school stomachs, dressing with care, picking jewelry, and going. One well-heeled foot in front of the other and too quickly I found myself at Fifty-seventh Street and Fifth Avenue, staring up at a façade of white South Dover marble, veined with city soot, that rose to a green-tiled mansard roof: my new place of work.

Bergdorf Goodman. Xanadu. Candy Land.

If there is such a thing as reality, this definitely wasn’t its home. Surrounded by the Savoy Plaza, the Plaza hotel, and the Sherry Netherland, it was a plush corner of the world even during the ’70s while much of the rest of the city was falling into dereliction and decay. With Bonwit Teller on one corner, Tiffany on another, and Henri Bendel just up the street, this was a land of old-fashioned luxury. The women who shopped at these places were not the sweater and bell-bottom set. They came to the store dressed with pantyhose, suits, mink coats in the winter, gloves, and proper handbags.

Inside, the French Renaissance interiors—marble walls lit by crystal chandeliers suspended from white cupolas decorated with oval painted miniatures—it all felt as if Marie Antoinette would pop in any minute for a hat fitting by Halston, the store’s head milliner. My pumps made an unseemly racket on the inlaid marble floor as I crossed this hushed temple to what I hoped would be a new life.

The elevator doors closed around me and opened again to the fourth floor: couture. I stepped out into restrained elegance, where the display cases and racks were spare to the point of empty—and vigorously guarded by ladies in all black: the vendeuses.

These experts at selling very expensive clothes to the carriage trade eyed me in such a forbidding manner that I truly considered turning right around and heading back down the elevator. To say that the vendeuses were unwelcoming to newcomers was an understatement, and I clearly posed a particular threat. Among their dark uniform style (they dressed somberly so as not to take away anything from the customer), I in my green suit stood out like a peacock. In my world black was reserved for evening, not daytime employment.

My throat choked with emotion and my stomach went on a roller-coaster ride as I tried to hide on the floor. Not long ago I was on the other side, a shopper being waited on by the vendeuses. Although that was another life, I hadn’t a clue how to find a place among these quintessential salespeople, subservient in their speech to customers and cutthroat competitive among themselves. I passed a stout woman whose severe updo matched her expression. Another, whose structured dress was the color of crow’s feathers, pursed her lips in disapproval. If only they knew. Surely none of these women had ever taken to their bed for a three-day crying fit after their daughter broke a front tooth at the playground.

I held my chin up high, my pose for getting through this life, and found a pillar to tuck myself behind. I didn’t have high hopes for my future at the store; I would be lucky to make it through lunch.

An unexpected tap on my shoulder nearly sent me through the roof.

“Scusi,” said a tidy man with salt-and-pepper hair while bowing apologetically for my jumpiness. If he only knew.

“My intention is not to disturb you, signora,” he continued. “My employer sent me over to talk with you. She does not speak English well. She is Signora Fendi.” The man waved a manicured hand over to the other side of the store, where an imposing woman in the finest Italian cashmere and wool was surrounded by a fluttering

team of people.

Of course I knew her. Anyone halfway interested in fashion knew Carla Fendi, one of five strong sisters who ran the empire they’d grown out of their parents’ original Roman shop where as babies they had slept in drawers and as toddlers used its goods as playthings. The business was truly in their blood, and they had done impressive things with it. In the mid-sixties, they’d hired a young designer, Karl Lagerfeld, who created a brazen fur collection with its own double-F logo, for “Fun Fur.” Through the rest of the sixties and early seventies, he imagined fur as no one else had—sheared pony-hair capes with oversize hoods in rust and extravagant black Mongolian lamb vests—so that Fendi became a necessity for the type who skied in Gstaad.

Ms. Fendi was in town to set up a new fur department at Bergdorf. Mr. Neimark had negotiated an exclusive deal with the store, which was quite a coup but also controversial. The Fun Fur from Italy was nothing like the rest of the stately fur department, where men came to buy their wives long minks or fox stoles. Amid her pelts sat Ms. Fendi with her walnut-colored skin and short, thick hair shellacked into an obedient helmet.

“Miss Carla Fendi would like to know who exactly you are, because you’re dressed so well.”

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist