- Home

- Betty Halbreich

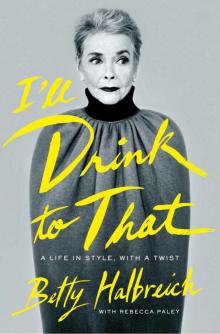

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist Page 23

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist Read online

Page 23

My clients often ask for advice on how to get rid of clothing. I always say to keep the beautiful pieces: embroidered, beaded, or one-of-a-kind looks. They are usually sumptuous and feel new when revisited. Treat them like lovely antiques. Most often the decision whether to keep or lose a garment hinges on size. Bodies change over the years. If you’re a size 14, the size 8 in the back of ye olde closet will never make it on the new you. Toss!

My biggest piece of advice for closet cleaning, however, is this: Do as I say, not as I do. I find tossing my own clothing so very hard, like parting with a favorite toy, or memories of what happened when I was wearing that dress. Many things raise their heads to this sentimentality. Every item seems to have a label attached, and I don’t mean Dior, Givenchy, or Galanos. Rather, my mother bought it for me, or it was worn with Jim during our last New Year’s Eve together.

I’m my own worst enemy. I even had trouble bidding adieu to my wedding dress—the one that began a failed marriage and that my mother-in-law returned to me the day I got back from the mental hospital. In order to let it go, I had to find a home for it, which took me many years. I tried everything and everyone to rid myself of the big white burden. It had little meaning yet represented something momentous. What’s in a dress anyway, worn for a couple of hours and rarely worn again? Enough that I spent a year convincing the Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota, home to a large period clothing collection, to become the final resting place of my wedding gown and veil.

I can afford to collect because I have the luxury of twelve closets. (Closet space is the one benefit of living alone.) That kind of storage space, which simply doesn’t exist in buildings anymore, is as anachronistically luxurious as the clothes they hold. (But, my God, do I need a Kenzo from my daughter’s wedding twenty-seven years ago or evening shoes I can’t get a toe into but are too beautiful to toss?)

Being very compulsive and single, I can arrange, rearrange, and do whatever I please. The closets in my bedroom, a world unto themselves, have shoe doors constructed in the 1950s by a closet shop—the kind we used in that era for custom hangers, poles to reach high places, custom-made molding and quilted cotton lining for the shelves, all done in the color of your choice. My beloved shoe door that holds about a dozen pairs suspended by the heels leaves the floor bare so dust bunnies do not gather.

The first closet, originally Sonny’s, has one long rod where I hang pants, each pair on its own pant hanger. Skirts, next, hang the same way. Long ago I found brace dividers that slip over the pole, with each divider holding three blouses, shirts, or cardigans, so that each garment does not get creased. On this gadget I hang all my shirts by color: white, colored, stripes, then prints. Above the rod there are two shelves that house handbags. The top holds large bags, baskets, or summer leathers. The lower has smaller handbags and clutches with two quilted boxes on either side for out-of-season items such as summer T-shirts or winter sweaters, depending on what month it is. All are very easy to reach.

The second closet in the bedroom, which has yet another shoe door to accommodate the shoes I wear every day, has one shelf in the back that houses absolutely nothing. Imagine that luxury! It is too high to put anything on, and I don’t need it for storage. Long ago I used it for hats, which I always hated and so never needed to reach. This closet holds my dresses. (I wear a lot of dresses if I can find them. If not, I constantly wear my old favorites Geoffrey Beene, Issey Miyake, early Michael Kors.) From a lower rod hang seasonal jackets—lightweight summer in the back, a bit heavier cottons in the front. I keep sachets on hangers often to divide: pants, sachet, skirts, sachet, et cetera.

If any of the clients I had admonished over the years for being the “more child” could see my bedroom, they would surely tell the physician to heal herself. For beyond the closets are three dressers, sitting side by side, where the goods inside them look as if they’re about to be sold, so exactly are they placed.

The first dresser is filled with curios: old belt buckles, Mother’s oversize silk flowers that I often pin on my lapel in the spring, change purses from my grandmother, a fan of black ostrich feathers that belonged to my great-grandmother, a handmade satin Geoffrey Beene belt, a scarf constructed of ribbons.

On to the second dresser, which houses scarves folded and stacked end up, like index cards in a library’s filing system. The second drawer is lingerie: nightgowns, underpinnings, and petticoats from my original trousseau. I tie them in bundles with ribbon and, just like Mother, throw in an empty perfume bottle for good measure. In the bottom drawer are summer pantyhose in bags and turtleneck T-shirts in all colors that my adorable household person has given me over the years. I often wear them under sweaters. Cotton is kind.

The third dresser is my playground. The bottom drawer holds the evening bags that are no longer practical for me as a single woman to use without the availability of a man’s pockets to stuff—including a very rare minaudière of real gold from Venice that was a fiftieth-birthday present from a mother who wanted me to have the world. I had some old diamonds I’ve never worn, so we threw them on the closure. I’ve never seen another like it.

I can’t tell you the jewelry I have that’s lying in gutters and taxicabs, yet there is still enough left over to fill the other two drawers of the dresser. Lucite trays hold wonderful pins, earrings, bracelets, and necklaces long and short—all laid out in a very organized way. Attached to everything, a story. There is the wild brooch of citrine, diamonds, and rubies in art deco swirls that my father brought back from a business trip and Mother hated. She told my father, who never bought her jewelry, “You must have done something quite terrible.” My big malachite cat that I bought as a young married woman perusing the shops at Henri Bendel stares out at me with its rhinestone eyes; every time I wear it, one of my clients says, “We have to make copies of this!” One year Kathy decided she loved buttons and turned a bowlful—military, Chanel, horn—into a bracelet that I still wear in the dead of winter. In my little jewelry pouches, I keep individual necklaces from the talented Meredith Frederick that have become a signature of sorts.

In the holy of holies, my battered blue jewelry box with B.H. in gold from my mother-in-law, I keep three gold watches: Mother’s, Sonny’s, and one that was a gift to me when I turned sixteen. I also have Margaret’s church amulet blessed by her priest that she gave to me when I was sick. The cook—who baked decadent chocolate cake for Sonny and coffee cake for me when we visited as newlyweds and cookies for my children when they were little people—comforted and saved me long after I had grown up. She loved my father so much that when he died, she refused to attend his funeral. Afterward she worked for her parish priests, who remarked that they never before had eaten so well.

I try not to let my collections languish—how quickly treasure becomes junk—but instead put them to good use. (There are some things I don’t house, like Frieda’s wedding ring, which I wear every day. She wouldn’t like that, because she herself wore it only on her weekend days off. Her white aprons, however, are still in the dresser drawer where she left them.) Sometimes that proves quite a challenge. I have a drawer full of monogrammed handkerchiefs—truly a thing of the past—that were made for my mother, my father, and me. I can’t throw any away, even the ones that have holes. Instead I fill them with lavender or rose petals, tie them into balls, and use them as sachets to line my drawers.

When Carol Luiken, now retired from costume design and living on Cape Cod, bemoaned the fact that she couldn’t find handkerchiefs anywhere, because she always carries real hankies, never tissues, I had an idea. Well, I had maybe fifty embroidered handkerchiefs with my mother’s name, Carol, and they weren’t getting any younger lying in my drawer. So I sent them off north, bound, of course, in ribbon and accompanied by a sachet, for a surprise Christmas gift.

Carol was thrilled with the beautiful hankies and even more with the thought. It is a pleasure to attach one person to another through an item.

I have often given what was new when purchased—a Chester Weinberg dress, a Comme des Garçons coat, a needlepoint handbag from Venice—to a young friend who looks so good in vintage clothes. I still wear the navy-and-white Geoffrey Beene dress that once belonged to my client Estelle. It gets better every season!

Not long ago, Dena Kaye—the daughter of the wonderful comedian, actor, singer, dancer, writer, and cook Danny Kaye—came to see me to find something to wear for an evening at Carnegie Hall in honor of her father. The upcoming public appreciation for her father’s many talents, which she felt was long overdue, made it a difficult time for Dena, who as one of the event’s speakers wanted something graphic for the occasion. We plumbed the store’s contents and came up with nada; she had her own very strong thoughts. Having known Dena for more than twenty years, I could sense she also wanted her clothes to pay tribute to her remarkable family. Why not wear something that had belonged to her mother, Sylvia Fine, a brilliant composer and lyricist who wrote many of her husband’s songs, I suggested. Of course, everything was in storage. So we agreed Dena would pick out what was salvageable, which turned out to be three huge garment bags that filled a fitting room. The garments were for the most part custom-made by the California designer Don Loper. Trying on all the very extravagant clothes was like internalizing a part of her mother. Finally we came upon a green-and-black striped full-skirted dress with a bolero to match. Finding the beautiful dress, fitting into it (the workroom performed a miracle), and looking sophisticated was a boost to her being.

Clothing is no different from traditions or memories; it’s a blessing when newer generations take them on happily. I love when children of clients pilfer their mother’s closet—same as I did to my mother’s wardrobe as a young person. That’s a true compliment to taste.

I now have three generations of clients. There are the originals, or what’s left of them anyway (fitting their walkers and wheelchairs into the dressing room is the hardest part!); their daughters, whom I knew as children and are now into middle age; and now their granddaughters.

I consider it the best commendation when I win over the thirteen-year-olds, because they’re my toughest customers. As soon as they enter my dressing room, I know they’re thinking, “No way this old lady is going to dress me.” My failproof method is to first send away the mothers, who nowadays hover and fret more than in the days when children got polio. I send these “helicopter parents” (a completely foreign notion, taught to me by my grandson) flying right out of my dressing room. These young people get to try their wings—and taste—with me. I will let them choose the outrageous, and I’ll pull what I believe is appropriate, and we end up sometimes in their corner, sometimes in mine. But the end result is always sheer happiness for both of us.

The young girls of today all dress way too maturely, but you can’t take one and make her stand out from the others in an adorable little chiffon dress. That would make for some kind of miserable evening! They dress for their peers—don’t all women?—not for what I or their mothers want. I forget my own daughter and her smocked dresses, another life, when a thirteen-year-old chooses a silver bandage dress. I simply do it in good taste and show alternatives. I try to steer them away from the herd and make them understand the beauty of individuality.

When we did a sequin dress for one of my long-standing clients’ granddaughters . . . well, her face lit up. And it kept getting lighter and lighter as we continued to make the dress shorter and tighter. She kept looking up at me in the mirror, and I kept saying, “That’s okay.” It’s dress-up. I don’t have a problem with it. I love that age group and what they have to teach me. They were the first who layered two T-shirts on top of each other, which I adore and utilize from time to time with clients of all ages.

I can still learn, even though Lord knows I’ve observed a lot over the years. Once, when a woman in the elevator found me familiar and asked, “Did you used to work here?” a buyer exclaimed, “Work here? She was born here!” (The reason so many people feel they know me is from my presence up and down all day in the elevator; I have considered wearing a red carnation and greeting people at the elevator banks, for all the times I get stopped.)

Indeed, it seems to many that I’m older and more steadfast than the limestone that makes up the store’s edifice. It’s been seventeen years since Jeff Kurland packed up his costume shop and moved to California, but whenever he’s in town, he always stops by the office, because I’m like “a monument,” he says. People from all over the country—Texas ladies who lunch, political types from Chicago, the wives of Oklahoma ranchers—do the same, because they know, even if we don’t find clothes, they’re going to have a great time—and I will give you lunch served on sheets of the store’s white tissue paper in lieu of a place mat (with not a linen napkin in sight!).

My longevity in a business where most things are in one minute and out the next is astounding, even to me. So many people have come and gone through my life. My goodness, the presidents I have reported to alone! I’m still very strict and disciplined in my work, but at this point I hearken to no man. (They’re scared to death of me here; that’s the fun part.) I have been at Bergdorf so long that it has become my store.

People often ask me the same question: “How do you do it?” I don’t feel so great every day. But just like Jeanne the fitter, I rise, dress, and am off to work, rain or shine. Aging can be scary if you let it obsess you. As soon as I turn the key in the office door, I’m alive and ready for the fight of the day.

Idle hands and brain make for unhappiness. I have known a lot of that. One exorcises the bad in pulling the heavy wagon. Everything must not be set and easy, otherwise life becomes sedentary. “Challenge” is the word. Some people do Pilates; I get under the bed and look for old Kleenex. Going to the gym to work out with a trainer is not stimulating to me. Walking through seven floors each day, arms loaded with clothes, is. (No wonder my doctor remarks on my strong upper arms. To this day he doesn’t fully understand what I do for a living.)

The last years have brought not only the aches and pains of old joints. They have also brought out the humor I’ve become known for. I no longer censor myself in any way. Some call my one-liners bluntness—maybe—but I find that in my dotage I like to leave people laughing, or at least bewildered.

A tech entrepreneur from Silicon Valley, and a new client, said, “Talk to me about color.”

“I like it.”

For heaven’s sake, I wasn’t going to give this woman a lesson in color theory. Instead I smoked out her true predicament, even though she didn’t know what it was. A woman in her fifties, surrounded at work by people who, in jeans and tight tops, were young enough to be her children, she followed their lead. In her mind it meant she had joined forces with the “youthful set.” But to me that was insecure and misguided.

I understood my client’s dilemma perfectly. I’m probably the oldest woman in the store. I could walk around thinking everyone around me is so hip. But I don’t. I like to be different—even if “different” means older and especially if it means better. (Of course, this is coming from a woman who thinks all the people at the store look like they’re going to the beach.) I have very high standards and want my clients to as well. There is nothing wrong with aspiring to an elevated style, the kind that has nothing to do with money or labels.

With my Silicon Valley entrepreneur, I let her have her jeans and tight tops (she had a figure kept youthful by much running). But I insisted, “You always have to wear a jacket.”

“You bring something to the table that your younger counterparts don’t,” I explained. “You have intelligence, beauty, experience. You should also bring something to the table in the way you dress.”

That’s when I slipped a sumptuous yet streamlined leather jacket over her. The entrepreneur understood immediately. She had come in for an evening dress and left with a leather jacket.

After saying good-bye to André t

he carpenter, I walk back into the office where Emily, my assistant, an unflappable girl from the Midwest, hands me one of those telephone message slips that I have come to loathe; they often read “Urgent problem!”

“Jimmy Fallon’s wife’s stylist is coming. She needs a black dress,” Emily says.

“Who?”

“Jimmy Fallon.”

“I don’t know who that is.”

“He’s on TV.”

“Oh, you know I don’t watch those reality programs.”

How much I have seen from my office—even the planting of what were once saplings and are now sprawling trees. Funnily enough, my dream of standing at the window with a gun is gone—dissolved—although I often think about it in my waking hours. I described it to Joan Rivers not long ago. Having run into her as she shopped for nightgowns for her sister, who was desperately sick with cancer, I brought her down to my quiet sanctuary. Somehow the subject turned to my rifle dream, which I made a joke out of; I’m not exactly a sheriff type. I simply wanted to provide a moment of distraction. Joan, naturally, had the last laugh. The next day a package arrived by messenger: a chocolate pistol and a card from her that read “Don’t shoot. Eat.”

Emily relays to me yet another message from My First Bride. (She has already called twice today. The first was about a dress with elephants on it that she saw in the store. A die-hard Republican, she said, “I think I should really have it.”)

“She wants to know what movie she and Jock should go see.”

“Oh, dear God. Information, please.”

Suddenly a voice, not unlike the sound of a car coming up a gravel driveway, rasps loudly from down the hall to my office: “Did you hear when the producer said, ‘Make the clothes believable?’ It always scares me when they talk like that.”

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist