- Home

- Betty Halbreich

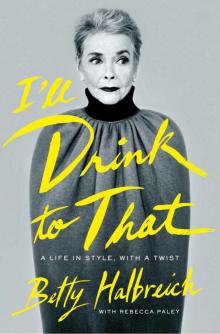

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist Page 7

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist Read online

Page 7

Everyone always thought New York was the place for fashion, except for my father, who said, “Do you think that Hattie Carnegie just makes clothes for women in New York?” It wasn’t the only place, but it was different from any other place. I had always marched to my own drummer when it came to dressing—turning my cardigan sweaters backward when I was a teenager because I didn’t want to look like everyone else, or pairing brown shoes with a navy skirt in a combination that most people assumed was mismatched but looked well on. They way I dressed myself was not unlike the way I’d dressed my dolls as a child. The pressure-cooker style of fashion in New York was a shock to my midwestern sensibilities.

And yet when I first arrived in this bewildering place, I took solace in shopping. Oppressed by the concrete landscape and not knowing a soul other than my husband’s family, I would take myself downtown and sit in Sonny’s office until it was time to go home. Out of desperation I learned my way around Macy’s antique furniture and china departments, choosing the famous store not for its clothes (I never looked at the clothes, which weren’t very up-to-date) but because it was across the street from the office. I spent many hours collecting Early American blue-and-white china that was more fit for a cozy country kitchen than for our first apartment on a nonresidential stretch of Sixth Avenue.

After the war, apartments simply weren’t to be had, but my father-in-law knew Ben Marden, who owned the Riviera, a famous nightclub across the river in New Jersey, where big names like Lena Horne used to appear. Marden also owned the building, on West Fifty-fifth Street, into which we moved. We were lucky to have it, but I didn’t feel that way. The apartment was small, noisy, and cramped with not a sign of green grass near it.

Housing was the only deprivation, for us, in post–World War II New York. It was as if someone had exhaled a lot of problems, and suddenly everything from cars to clothes were back in abundance. The city seemed to be awash in money. We went to restaurants and nightclubs every weekend, with dinner parties at home thrown in during the week. “We” were a large group of Sonny’s acquaintances (that got larger every night out on the town) who all had families, careers, and intimidatingly full lives—and they were almost a decade older than me. There was Charlie, who had a marvelous time partying with Sonny during the war, and his then wife, Charlotte; Jerry Silverman, another wartime buddy and owner of one of the country’s most successful dress-manufacturing businesses (which he described as the “meat and potatoes of the dress industry, not the frosting”), who threw fun, decadent parties with his partner in their lavish penthouse apartment at the Mayfair Hotel (the terrace was carpeted with a Persian rug), where people from every walk of life (even the clergy) attended; and Sidney, who knew my father from the fur business. Sidney and his wife, Beverly, introduced me to Claire and her husband, Ted. Claire, extremely intelligent like her husband, had a steel trap for a mind. We used to rent vacation places in Atlantic Beach together.

On Sonny’s arm I was just along for the ride. (Although he never let anyone get too close, everyone just adored Sonny.) But what a ride! Evenings out started with food, heaps of it. Every meal was a fiesta. There was the wonderful Italian restaurant, Romeo Salta, where pasta was prepared right at the table so that it could be eaten hot and al dente. Brunch at the Colony, “the boardinghouse for the rich,” might be eggs Colony (a piece of toast, freshly cooked crabmeat, a poached egg, and a few drops of sherry) and then back for a dinner of truffled salade à l’italienne and chicken Gismonda. Just around the corner, on Sixty-third Street between Madison and Park, Quo Vadis served marvelous sunset salad, poached oranges, and chicken Quo Vadis. Steak Row, the neighborhood in the East Forties with so many steak houses—the Palm, Joe & Rose’s, Danny’s Hideaway—had its beginnings back in the 1920s when a former plasterer from Italy named Christ Cella opened a small basement kitchen in an apartment house. His eponymous restaurant grew into an institution where Frank Costello and Frank Erickson had a great, large table outside the kitchen. Right next to these fine fellows, who ran huge gambling empires, one could find us on most Friday nights, eating huge chopped salads, overflowing platters of french fries and onions, and steaks on the bone.

However did we go on to late-night entertainment following such feasts? Afterward there were exciting evenings at the Plaza Hotel’s Persian Room watching the Williams Brothers and Kay Thompson, who seemed eight feet tall, with the largest hands I had ever seen. At the Waldorf Astoria’s Empire Room, Pearl Bailey sang her heart out and danced around the stage while the man who would become her husband, Louie Bellson, played the drums.

We practically lived at nightclubs like the Copacabana, El Morocco, the Stork Club, and the Latin Quarter (opened by Barbara Walters’s father, Lou), where all types mixed and the legendary acts performed in the ultimate café society. At the Versailles we watched Edith Piaf, frizzy-haired and very unkempt in a black dress with cigarette ash down the front (not unlike Nana), sing plaintive songs that, although we didn’t speak French, moved us. Ben Marden’s Riviera across the river in New Jersey was large but gathered the best. It was there that Lena Horne’s beauty first astonished me. (Many years later I saw her in Bergdorf’s wearing large glasses but underneath her age still an incredible beauty.)

No matter the cabaret or restaurant, we always had the best table. There was a lot of greasing of palms that went on. Hail-fellow-well-met, my husband knew every captain in town. That kind of access meant we secured a front table at the Copa by entering the Wellington Hotel next door and walking through the basement alongside showgirls on their way to work at the nightclub.

The fun didn’t end after dancing and a show. Then we headed to after-hours clubs like Gatsby’s and Billy Reed’s Little Club, where until very, very late we would sit on banquettes, drink, eat yet again, and rub elbows with early TV personalities and film people. Sometimes we did more than rub elbows. Once, at the Little Club, a hand gripped my neck and a deep baritone voice said, “You are some cute girl.” Sonny shot up, seized the owner of the hand by the shoulder, and was about to give him a wallop just as the captain and a few of the waiters pulled him back. The cheeky fellow whose idea of hitting on a girl was grabbing her by the scruff turned out to be David Susskind, the notorious womanizer and legendary talk-show host whose program, which aired for thirty years, featured everyone from Nikita Khrushchev to Truman Capote.

Many a night Sonny and I heard the clink of the milkman’s bottle deliveries as we made our way home. I didn’t have to rise early. I lolled in bed until 10:00 A.M., taking breakfast on a tray just like Mother and Nana. Using half of the breakfast set for two that I’d received for my wedding and the three-division pot for cream, coffee, and sugar, I sat on the end of the bed with the telephone and a cigarette. My only responsibility was to find enough outfits for all these evenings. The task, however, quickly became a full-time job, because we really and truly dressed up to go out: all manner of cocktail clothes, satins, peau de soie, lace, cinched waists, off-the-shoulder, lots of sleeveless, diamond buttons that you were always losing. And you didn’t wear the same thing twice (at least not in a way anyone would notice).

In the hunt for beautiful clothes, nowhere was off-limits. A few blocks from home, I journeyed to Bonwit Teller, a traditional store that had just about the same clothing as every other place of its ilk, but I returned again and again because of a funny and wonderful saleswoman on the sportswear floor. Hope, handling three to four people at the same time, threw her customers into a dressing room and piled the sportswear on them. It was “hard selling,” but she got away with it using humor. The hours the woman put into that store! I never understood how in the background there were a husband and a child. Selling was her life, as it was for so many others in her profession at that time.

About twenty blocks south on Fifth Avenue, Lord & Taylor was one of my favorite shopping experiences in New York—thanks to Mrs. Lamm. Charlotte, who was becoming a dearer friend all the time, and I made a day of it, just a

s some people go to museums. We started on the fifth floor with lunch at the Bird Cage. In armchairs with connecting trays, we ordered “society sandwiches” of shrimp salad, cucumber, chicken, and date-nut bread with cream cheese; a salad that came with an ice-cream scoop of cottage cheese, egg salad, and tuna salad on top of greens mixed with beets and shredded carrots; or strawberry custard from rolling carts modeled on Italian race cars. (The store’s restaurant also served coffee, juice, or bouillon when it was cold outside to the shoppers who arrived daily at the store before it opened.) After lunch Charlotte and I went through the furniture department, then clothing and accessories with the savvy Mrs. Lamm, who put away expensive Ben Zuckerman suits for us until they went on sale.

The real treasures, however, were at Loehmann’s. We journeyed to the site of a former plumbing store in the-middle-of-nowhere Brooklyn, where Mrs. Loehmann ruled her dressing-room-less empire from a chair overlooking women trying on the high-end fashion samples and overstock bargains right out on the open floor. Smoking from a long cigarette holder, Mrs. Loehmann brightened up her all-black ensemble—black silk stockings, black kidskin lace-up boots, and a black silk dress—with blue eye shadow and a bright pat of rouge on each cheek. With only the store’s banquettes (in the same striped zebra material used by El Morocco) and gilt furniture to rest my purse and clothes on, I found many treasures, including a Norell checkered wool dress and a bolero jacket that still had the name of the model who wore the sample sewn into the garment. At ninety-nine dollars, it was expensive enough that I knew Sonny would murder me for buying it. Even though Loehmann’s was known for its discounted merchandise, this was high couture—and couture, even at a bargain, is no bargain. I was used to a father who was thrilled to buy me beautiful clothes and still hadn’t habituated myself to my husband, who, although his mother racked up huge bills at Hattie Carnegie, wasn’t crazy about it when I spent money.

But if I released the Norell from my grasp, the dress would be snatched up in a second by one of the women circling like vultures. This was a model, a one-of-a-kind that hadn’t even been manufactured. (I wore it for an elaborate Easter brunch at the St. Regis hotel. Although it snowed that day, I was determined to wear it, and I did—and I froze.)

Accessories were absolutely irresistible at Henri Bendel after the fashion-forward Geraldine Stutz, an early proponent of Perry Ellis, Jean Muir, Sonia Rykiel, among many others, took over the shop and turned the main floor into the “Street of Shops.” In the hours I spent poring over the little glass cases of jewelry, handbags, gloves, stockings, and scarves, I found a marvelous cat pin that was a real conversation piece. Made of mottled beige- and caramel-colored plastic with ersatz diamond eyes, the sitting cat takes up an entire lapel of a jacket. I thought that with a price tag of twenty-five dollars, it would get me my first divorce!

Treasures lurked all over the city. Mme. Isabel—a successful opera singer in Germany until she refused to join the Nazi Party and had to move to New York, where she survived by decorating sweaters—created a fashion of embellished knitwear. Queen Elizabeth was a fan of her exquisite cardigans adorned with fur, embroidery, beads, sequins, and ribbons. I liked to wear those divine tops with accordion-pleated skirts designed by Stella Sloat.

More used to life in New York, I turned from the quiet seriousness of my Chicago roots and dove into the local sport of style. There were bragging rights to be had as the first to stake claim to a trend or to find a new place. Although I didn’t have too many friends, what they wore was very important. Each of us dressed to see what the other was wearing—and no one wanted to be outdone.

I wore a smart suit of red plaid by Davidow, which copied all the best French designs, for a shopping trip downtown. To a luncheon of cheese bread with egg salad and iced tea at Schrafft’s, I chose a coordinated cashmere cardigan sweater set, a knee-length skirt, and David Evins pumps. For the same Easter lunch, I donned the Norell checkered wool dress, and the inspired florist Judith Garden, whose arrangements incorporating unusual materials and containers broke the mold of conventional formality, made me the most wonderful hat of gardenia leaves. A living chapeau: I adored its extravagance.

This is how we moved as a group. We didn’t have a lot to do as married women, so instead we shopped till we dropped. A sweeping dress became an expression of one’s ability, a jeweled necklace of one’s worth. With an absence of other goals, clothes became our only markers for success. In other words, dressing became very competitive. And no one was more competitive than my in-laws.

My mother- and sister-in-law were the ultimate clotheshorses. Millie, an über-sophisticate, spent her life dressing to go out to restaurants and clubs. With her equally dashing husband, she led the nightlife in chiffon gowns by Galanos, Norell, Bill Blass, and all couture designers of the time. The combination of her stunning evening clothes and dazzling beauty turned even the most jaded heads.

Every spring my mother-in-law shopped for new hats with Mr. John, one of the most important milliners in the world. Florence also wore jewelry. Real jewelry. The era was about diamonds, not a great deal of color. She and her friends had diamond bracelets they called “stripes” that marked the length of their service to less-than-perfect husbands. Diamond and emerald drop earrings so heavy that they pulled on lobes and fifteen-carat diamond rings made up for a lot of bad behavior. I heard whispers that my father-in-law, who certainly spent more time at the racetrack than at home, had liaisons. I turned my head off to that, but Florence did have a lot of jewelry.

Many an afternoon my mother-in-law could be found at Hattie Carnegie in the East Fifties, where it was said that a lady could be dressed from “hat to hem” (she didn’t sell shoes). Although Hattie, a native of Vienna, could not sew or sketch, she built a fashion empire on her own good taste. Her workrooms—where by 1940 she had more than a thousand employees making her custom clothing and ready-to-wear lines—became a breeding ground for designers. Norman Norell, Claire McCardell, Pauline Trigère, and James Galanos all began with Hattie, who created a style that was truly elegant and très cher. There were all manner of beautiful pieces, but her tailored suits, tight-waisted and cut high under the arm to make one look smaller and younger, were the thing. I sat through many fittings of my mother-in-law’s suits at the store, and on one of these occasions Millie, who was very good to me, embarrassed her into buying me a gorgeous mauve tweed suit, which I treasured because it was my one and only.

Millie looked out for me like a big sister and worked all the angles as only she could. The Hattie Carnegie suit was wonderful, but the apartment she negotiated for us in the Park Avenue building she lived in was truly amazing. That Millie and her husband had an apartment on Park Avenue was a miracle of connections in itself, but when she told me she had procured an eight-room apartment on the other side of the building for Sonny and me, it excited me beyond anything that had previously happened to me in New York. Apartments, particularly ones as gracious as this, were still as scarce as hen’s teeth in 1951—and I truly wanted a proper home, like what I was used to, for our family, which now included a baby daughter.

Millie—a gambler like her father (and like the man she married)—traded in luck. Cardplayers who liked the high life, they lived under the code of what comes today could and probably will be gone tomorrow. Otto adored his kindred-spirit daughter and made it obvious in any way he could that she was the shining light of the family. Whenever they danced, he spun her around as if she were the only woman in the room.

In a stance perhaps born partly out of his father’s favoritism, Sonny sided with his mother, who, despite indulging herself in her unhappiness through precious gems, furs, and couture clothes, was at heart conservative. (She built a secret nest egg by peeling bills from Otto’s nighttime stash on the dresser, which took care of her in the end of her long life.) Both Sonny and his mother had a cautious bent that came from the fear that all they had could be gone, and quickly. They weren’t entirely paranoid. My f

ather-in-law was very much his own man and shared very little about his finances. He was a huge gambler and took many chances with the family fortune. As these types do, my father-in-law had to bet it all when he thought he had a winner. The business was always there for him to recoup any losses, so that no one ever seemed to suffer.

Even so, when Sonny and I walked into the sprawling and empty Park Avenue apartment, he demanded to know, “Who in God’s name is going to furnish this?”

We had screaming fights about the furnishings and the monthly rent of $225. Always the first to reach for the bill at the Colony or the Copa, he had enough money to be a sport but not buy furniture? Sonny said I was overextending him. I didn’t care how angry he was. I was a twenty-three-year-old mother of a toddler, with another baby on the way, and as far as I was concerned, we needed the space.

When our first child, Kathy, was born two and half years earlier, I marveled at how such a tiny person could take up so much room. I shouldn’t have blamed her; it was really the fault of all her accoutrements. Before she was born, I had an appointment at the layette department at Saks Fifth Avenue to assemble diapers, bibs, sleeping gear, and blankets—all of which was not delivered, done up in pink ribbon and piled into a bassinet, until the store got a call from the family that the new arrival had indeed arrived. (Many times I have duplicated this for clients who have babies by picking out layette items and folding them in a basket adorned with a ribbon and a sweet stuffed animal stuck in for good measure.) Kathy’s Silver Cross pram was like a parked car inside the apartment. We dressed our carriages like beds, with embroidered sheets, monogrammed pillows, and blankets of wool, also monogrammed, navy on one side, light blue on the other. It took so long to get the baby all plumped up inside that by the time the carriage was down the elevator, it was time to turn around and come back.

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist