- Home

- Betty Halbreich

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist Page 14

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist Read online

Page 14

“I can’t be with you right now,” I said. “Please, make an appointment, and I will be glad to help you.”

The woman, however, didn’t budge. She stood outside the fitting room where I had closed the door on my other client, literally pouting. All that was left for her to do was stamp her foot and whine, “I want it now!” If she was going to act like a small child, then I had to be the mother, tilting my chin up and clasping my hands below in an I-mean-business stance.

Maternal figures don’t just comfort and nurture; they also set limits. In my business this is as essential as working a zipper. Far too often when I’m out on the floor I witness abrupt and irate customers treating salespeople rudely. It’s an unfortunate truism that some believe that when they spend a lot of money, the sale automatically comes with a servant. Whenever someone like this takes out her frustrations on my co-workers or me, I often wonder if it’s because she can’t do it at home.

In my little domain, I always have a retort to plug up the mouths of the ill-mannered. I had a successful writer client who once brought a man with her to a fitting. She tried on all the clothes for him. But unlike Mrs. Ford, for whom seeking her husband’s opinion was clearly an act of communication, this woman was parading around like a chorus girl. This was an act of seduction, during which I might as well have been invisible. At the end of the show, I asked her if she wanted to keep any of the items she had tossed around, to which she replied dismissively, “I’ll let you know.”

She didn’t even afford me the dignity of looking at me while addressing me, choosing instead to make moony faces at her friend.

“If I do get anything, I’ll need it sent by Thursday.”

Later, when she had her secretary call, I insisted she get on the phone.

“You know,” I said to her, “I hold my knife and fork the same way you do.”

Deflecting the less savory parts of my business in an intelligent way diminished them and made room for the best part of the job, which was improving the lives of women through their costume. I dove into the task every morning by first walking through the store—back rooms and the floor alike—to hunt for a special item that might solve a problem or bring someone a bit of contentment. Part of this ritual was to keep me from clothing boredom. As I said, new clothes don’t arrive every day, and I always hope to find something overlooked (or kept hidden for a special client by a clever salesperson).

I also tested myself with each pull. Am I repeating myself too much? If I noticed a favorite dress from the season in the lineup of too many clients, it was a signal that my taste was getting in the way of dressing these women. I take it as a solemn vow that each person is an individual—even when a client comes to me looking to transform her image, as so many do.

While reinvention is hard in any context, in the fitting room it can be excruciating. My ladies say they want something new, but once they stand in front of the mirror naked to the world, they battle physical flaws, real or perceived. In that moment they return to their security blankets (famous labels, expensive price tags, the color black) and rules they came in with (no bare arms, only vertical stripes, black and navy clash). Taste changes at best gradually. You can’t move someone from a tailored human being to a fluffy dress with spangles. You may get her to give up the blazers and suits every now and then. Maybe.

I wanted the women who entrusted themselves to me to break out of their own molds and wear navy with black, go sleeveless, or break up ready-made outfits by pairing the designer separates with items from—gasp!—their own closets. But while they stood in such a vulnerable pose, how could I encourage my clients to be adventurous?

Through experiment, instinct, and experience, I developed my unique method of selling clothes. On top of the gifts I inherited from my fastidious and well-appointed childhood, I put the listening skills I learned in Margaret’s kitchen to use in my fitting rooms and amassed a trove of information about my clients from their own mouths. To help women move their style forward while still retaining their identity and comfort, I took a triangulated approach—the classic threefer, if you will. I generally pulled three groups of items: those that were too easy, those that were too hard, and something in the middle. The line of attack worked especially well with people who when they came to me were as unsure of themselves as a fawn on new legs.

That was the case with a mother of four in from Charleston, South Carolina, searching for the right gown for a fancy ball back home. With red hair, porcelain skin, and a perfect figure, she could have worn anything; I chose three stunning gowns, all very different from one other. She instantly took to the most traditional, a peony-print chiffon with cap sleeves and a waist-cinching belt. Very lovely and sweet, just as I surmised this southern belle had been brought up to be. I went in a completely different direction and put her in a gray, sleek, defined dress of my choosing.

“Nobody else at the dance would wear this dress,” I said to her size-2 reflection.

The dress was extraordinary on her. She looked like Jean Harlow. The three pieces of satin were utter simplicity save for the encrusted front. She said her husband would love it, but I could tell from the slight collapse in her bosom that she wasn’t comfortable.

“You can’t go to these things and not be comfortable,” I said, unzipping her. (I tell all my clients that you should love yourself in something immediately; nothing gets better the more times you look at it in the mirror.) “If you can’t dance, sit, or be comfortable with your friends, you’ll blame me for it.”

She put on the printed chiffon, which could have been her coming-out dress, and asked hopefully, “What do you think?”

“The truthful answer is: This dress is not how I envision you.”

“But it’s so easy.”

“That’s the problem. It’s too easy.”

She ended up with the second dress of my choosing: a fire-engine-red halter dress that wasn’t as clingy as the gray but pushed her slightly out of her comfort zone. This delicate young mother wasn’t willing to take the full risk this time, but I had rattled her chains.

If any of the salespeople on the floor had been present when I steered my client away from the printed chiffon, they would have sent me back to Payne Whitney immediately, for it was by far the most expensive of the three dresses. Working on salary as opposed to commission meant I had the freedom to offer clothes based on taste and feeling rather than the dollar figure on their tags. (When I’m selecting, I never look at price; I already know that everything here is expensive.)

I didn’t want to become an accountant. Still, I did keep an eye on how much my clients spent, although not in the way of most salespersons. Twenty years of living in this city of indulgences couldn’t beat out the strong roots of midwestern conservatism planted when I was a child. I understood the pleasure of wearing something new. However, when luxury veered into excess, I put a stop to it immediately.

That’s exactly what I did with the expansive wife of a Dallas developer who had made his fortune in real estate. She laughed easily through her fall-season shopping that resulted in two suits, some cocktail dresses, one long evening dress, three daytime skirts, a lounging robe and nightgown, a red python envelope purse, the most wonderful double-breasted cashmere coat with fold-up cuffs, and shoes for evening, day, and cocktail. Cristina was writing up the very long sales slips, and I had poured the fun, chatty “patient” some of our armoire wine when her face lit up with a revelation.

“Betty! But we aren’t done. I need a fur coat!”

A fur coat? I didn’t care if she lived in Alaska, let alone Texas, I couldn’t. I just couldn’t. A fur coat was the kind of big-ticket item most salespeople kill for, but it only gave me a case of the school stomachs. Memories of my old life returned as I pictured her unpacking all her purchases at home. Where was she going to hang everything? What was he going to say? No, no, no. Not on my watch. Closets can be too full. There is a point

of saturation.

“Aren’t you thrilled with we’ve done?” I asked. “Because I am.”

She had bought a new and extensive wardrobe for the season. Need, however, meant something incomplete. This wasn’t about need. Nobody goes naked. “It’s enough for now. There’s always a tomorrow!”

She gave me a wide-eyed look (which is not an unusual response to the things I say). In my little corner of the store, I’m direct and truthful—two words not normally associated with the world of retail. I don’t flatter or make nice-nice. There are many ways of selling, one being to repeat incessantly, like a trained parrot, “You look beautiful,” even if it isn’t true. I would rather have scrubbed the store’s floors.

I became known for not having pulled up a zipper or buttoned a shirt before uttering, “Take it off. It’s dreadful.” My old friend Charlotte had only one arm in a dress when I ordered her to remove it at once.

“But, Betty. I haven’t even put it on.”

“It’s terrible. I can tell in a heartbeat.”

A no was as good as a yes in my book. I wasn’t beyond letting a client walk out empty-handed. An appointment was a failure in my eyes only if the woman didn’t walk away feeling better than when she came in. That was challenge enough with all that people have to endure.

In meeting this challenge, I became more than a master of fit and a guardian of color. I also learned how to read expressions and minds. When a client, a successful painter, didn’t respond to the charcoal gray jacket with strong shoulders and the slouchy yet flattering black pants I put her in, I knew that something was wrong. Spunky and inventive, she loved to play dress-up with me. In this moment, though, she was somewhere else, and it didn’t look to be a good place. After not much more than a “What’s going on with you?” (it never takes a lot of prodding in my fitting room for the truth to pour out), she explained that she’d had an abortion. “I just don’t feel like myself,” she said. I knew what it meant to be unsteady as self-doubt made you unrecognizable to yourself.

I tried to send her home. Her intimate revelation rustled up something in my brain that I wasn’t quite comfortable with: a dim memory of waiting for my mother outside on the porch of a terrible place with her sister-in-law, returning home to friends who took care of her, and hearing that word “abortion” in whispers. I was one of those kids with an ear to the keyhole.

My client didn’t want to go home; she wanted to continue. So I took off the power suit and returned to the floor. I had no other choice. Remembering the friends who’d rallied around my mother, I pulled a wonderful jumpsuit, over which I threw a beautiful black taffeta coat with puffy sleeves that she didn’t need. She brightened as we experimented past the clean, monastic lines she typically favored.

“I just hope you know yourself when you get home,” I said.

The woman had come in not feeling well and left feeling much better (and poorer). No matter my own doubts about any situation, I never lose sight of my place in that fitting room: to leave my clients more self-assured when they walk out than when they entered.

To that end I respect vanity without catering to it. I always blame the dress rather than the person. Never “That looks awful on you.” Rather, “The dress is awful.” I say what I really think, not to be hurtful but to keep clients from feeling they don’t look pretty in front of their mirrors at home.

I’m not in the business of stuffing closets with useless items—indeed, my motto is this: I don’t dress closets. I don’t come to work to create fashion plates either. My role is to offer people permission: to be catered to individually, to treat themselves to something beautiful, to be important, to feel better.

I gave permission to anyone I got into my clutches, rich or poor, important or unknown. I even gave it to Cristina, who grew up believing that looking in the mirror was not a good thing to do because her mother never did it. Underneath her casual uniform of a Brooks Brothers shirt, a pair of pants, and a sweater, I had detected a hint of interest in her reflection. So, like any good surrogate mother, I nagged her. “Come on, Cristina,” I said. “You can do better.” My commentary wasn’t a put-down but a supportive promise. I wanted her to know that she could take care of herself without egotism.

The promise was delivered in the form of a coat I convinced her to purchase, which took no small amount of persuading. Even with her employee discount, the prospect of buying the luscious Italian camel cloth coat was unfathomable. “It’s way too expensive,” protested Cristina, a girl from Cheektowaga, New York, who couldn’t imagine herself wearing designer anything. “You have to have this coat,” I said firmly.

“Oh, God, I love it,” she said when she saw herself in the coat that she still wears—for better or worse—to this day.

That was the magic word. Love. I wanted women to love themselves instantly when they put on a new coat, dress, or whatever. Having established that a human didn’t need more than one outfit to wear and another while it was at the cleaner, what else was the purpose of buying all these clothes? To face the world and feel better. That was my challenge. Pairing a shirt with a pair of pants and throwing a sweater on top so that someone walked out with a new outfit didn’t mean much. But when I watched a human being’s face in that universal expression—“I really love this”—the feeling that she carried out with her purchase carried on in me as well.

Helping women with their wardrobes gave me some self-worth, which was a new feeling for me. Working also kept the loneliness I felt when I was home at bay. My old friends called to ask me to dinner or for weekends in the country, but they were part of couples with summer homes and more complete personal lives than I had. The store gave me purpose and a safe distance from which to watch everyone from my past go on without me. I was at work while the whole family attended the wedding of Sonny’s niece at the Pierre just two short blocks away from my office window. I pictured them and all their diamonds trooping into the hotel, and then I turned the store into my own personal park where I walked miles without ever being alone. It was psychiatric heaven.

I never felt alone at work, and not just because of Cristina sitting knee to knee with me at the same table or the wide variety of women dropping into my department at any given moment. I had come to the store at a wonderful time of new beginnings.

Like me, the carriage trade was being transformed. Mr. Neimark gathered a young, talented, and experienced group of managers and buyers to overhaul the merchandise as well as the physical store. That included adding an escalator, during whose installation he liked to shout at me from the bottom, “I put the escalator in for you, Betty!”

The changes didn’t happen overnight but were exciting. The escalator wasn’t the only innovation; style itself experienced a major upheaval. Up until the late seventies, the majority of department and specialty stores carried predominantly American designers. The styles that were fitted on European models did not fit American women as well as homegrown designs did. Plus, there was still a belief that buying American-made products was the right thing to do. In the eighties, though, the store went in the opposite direction and devoted the whole of the second floor to new talent discovered abroad. These foreign imports included the exceptional tailoring of Giorgio Armani and Thierry Mugler’s tight, curvy, and way-out dresses. The second floor was filled with the outlandish. There were Claude Montana’s monstrous shoulders and military looks, as well as big plaids by Jean Paul Gaultier, who believed that the strange was beautiful, too.

Maybe so, but the strange wasn’t an easy sell. The store became known as a vanguard of style; nonetheless it took a while for the customer to get used to this whole new avant-garde look. With more casual pieces rather than ensembles and more layering, it was the beginning of fashion as we know it today.

The new buyers and executives all had a sense of experimentation that I admired. I found camaraderie among these women, who were younger than me and very different from anyone I�

�d ever known. Some had children, some didn’t. They were single, divorced, in relationships. But all of them had worked most of their lives.

The best-looking and quickest-moving of the bunch was Susie Butterfield, the store’s publicity and special events director. I kept seeing her out of the corner of my eye, pushing furniture with the cleaning staff, rarely giving a smile, intent upon her job. PR work is never-ending, and you really have to stand apart from the others. I began following her when she was “touring the territory” and found we had a lot in common. Susie picked out the best and most expensive from nowhere, and we became fast friends. The parties she held for the store were legendary—people remember them still. (Her last hurrah, before she left after having a child, was a Fendi fashion show where she turned the Pulitzer Fountain into a runway for the models. The extravaganza was a grand exit.)

Before she left, however, Susie or one of the buyers would call at the end of a long, harrowing day to say, “Let’s go have Japanese food.” Off a group of us went to a comfortable little restaurant on the East Side that was nothing special but where they knew us. Not nearly as insular as my married friends, they weren’t interested in the useless life of lunching, dinners, and dressing that had once made up the core of my existence. In these smart, ambitious women, I saw a reverse of my old self, the person on the other side of the mirror. Their confident example was an inspiration, their casual invitations to dine my biggest comfort.

Corinne, who was part of this close sorority, called at the end of one day to ask me out for a drink before her trip to Europe the following day. In the middle of our conversation at a bar near the store, a man approached us. He had a round, ruddy face, glasses, and white hair that must have been bright red when he was young. In his tweed jacket, there was a silk paisley pocket square, the only sign of dandyism in an otherwise elegant but conservative outfit.

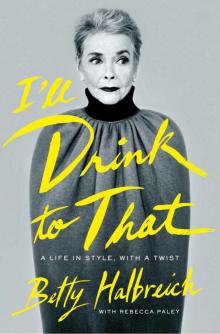

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist