- Home

- Betty Halbreich

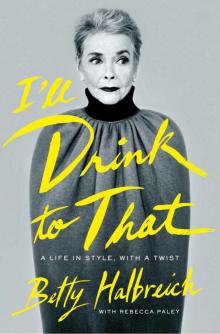

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist Page 15

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist Read online

Page 15

“There’s a man at the end of the bar who would like to meet you,” he said to me with all the cool of someone with a gun to his back.

Corinne, truly a romantic, interjected, “Your friend? Well, what’s wrong with you? This is my friend Betty.”

I was absolutely humiliated. Still, not one to be rude, I made small talk with the man, whose name turned out to be Jim. Quite the sophisticate, I asked Jim if he liked movies. I couldn’t think of anything better. Yes, he said, he liked them.

As we learned, the poor, newly divorced soul wasn’t out of the house a week. That didn’t deter Corinne, who whipped out a card on which she wrote my name, address, and telephone number!

Jim took the card rather sheepishly and called me the following day. I wasn’t convinced. In Philip’s office I explained why it was a bad idea.

“We’re from two different worlds. He’s Irish Catholic,” I said.

“I don’t pick men up in bars,” I said.

Philip, always pushing me to break the Sonny habit, said, “You could step off the curb and meet someone, you know, Betty. Why don’t you brace yourself and try it?”

I returned Jim’s call and made a plan for him to meet me at the apartment after work. Then we could go from there to dinner somewhere in the neighborhood. I answered the door when Jim arrived, and the expression on his face was priceless. To begin with, he had never been in an apartment on Park Avenue, and certainly none that size. I put him at ease, for I was as frightened as he was. I poured him a scotch, and things became more relaxing.

If finding a different human being from Sonny was the medicine, Jim filled the prescription. Retired from a lifelong career in the insurance business, he was slow and methodical in everything. Where Sonny didn’t care a whit about clothes, Jim loved to dress. He was a real Ralph Lauren model in his wonderful tweed jackets, great neckties, sweater vests, pocket squares, and argyle socks. Tall and stocky, he carried his clothes well. But what really impressed me was how well he kept them. He had twenty-year-old coats that looked as good as new.

Jim was impeccable, dependable, and lovely. The sweetest human being on earth—there were times I could have massacred him. While I was very quick, he was incredibly slow. In the time it took him to put on his shoes, I would be fully dressed, made up, hair in place, pocketbook organized, ready to go, and going out of my mind. I recognized, though, that the balance was good for me and began to learn tolerance from him.

When he found out I didn’t have any insurance on my apartment, he set me up with a renter’s policy. I knew nothing. Jim introduced me to a money manager and the concept of saving for retirement. Sonny, who’d left my weekly allowance on the dresser, never let me have a bank account. Jim went with me to the manager’s office every quarter and patiently taught me how to build a nest egg. (I must say, to this day I really loathe doing my bank balance and writing checks—all due to my lack of mathematical skills.)

Jim showed me many things that no one ever had. I had never paid an electric or a telephone bill. He documented everything for me and then taught me how to keep manila envelopes to house them. He goaded me on to ask for a raise when I, too afraid to upset the applecart, was content to sit back and wait for one. (Good thing, or I’d still be waiting!) From childhood to child bride to a childish mother, I had always been taken care of. Always. That was a lot of growing up to do for a woman in her forties. But I had finally found a person who believed in my potential.

Jim made me more independent as we fell into a comfortable routine that began on Friday afternoons when he drove to Manhattan from his home in New Jersey to pick me up and shepherd me back there with him. We had the same fight every Friday at three o’clock. “Why aren’t you ready? I don’t want to go back in the traffic,” Jim complained. And every Friday—in traffic—we returned to the simple condominium with a wood-burning fireplace that we put together.

My life in Clinton, a sweet town on the Raritan River with cherry-tree-lined streets, picturesque old mills, and a real Main Street, was blissfully isolated. In his cozy little apartment, surrounded by Early American finds, I spent weekends cooking for him, driving him crazy that he didn’t vacuum or didn’t make the bed right, and doing little else. He was not big on friends. He had a few that went way back, but Jim didn’t require much in the way of a social life. Another only child like myself, he was content if he had a book in his hand (he relished detective stories, as did my father) and me by his side.

My weekend life was another playing house, which I just adored. I made Jim chauffeur me (I unfortunately never learned to drive) to an incessant stream of farm stands. “Betty, if I see one more strawberry . . .” he threatened. But he never refused me as I went straight into the strawberry patch, unable to pick enough of them, while he sat in the car reading the New York Times.

In that little apartment facing the pond, I made jam, pickles, and many of the foods of my youth. In the summer we had salads with fresh herbs and Jersey tomatoes and pickled peaches from the orchard served over ice cream. In the winter there were stews with sour cream and noodle pudding. We had his next-door neighbors over, because they knocked and asked what we were cooking—it smelled so good. His old pals came occasionally for an early supper of German potato salad and cold roast chicken or a brunch of eggs Benedict.

We made a good team. Jim learned to grocery shop. I told him what to get during the week, and, being frugal, he waited for the specials to buy the items. Jim measured all my baking ingredients, because I do not measure well. I put them together, and out came cakes, pies, and chocolate rolls. He loved to make biscuits or pancakes in the morning to surprise me.

Grocery stores, farmers’ markets, and the occasional outdoor church sale were the extent of my shopping desires. I’d spent enough time in Macy’s furniture department during my twenties to fulfill a lifetime of antiquing, and working all week as I did in the candy store, the last thing I wanted to see were clothes. Jim, however, did insist one time that we go to a mall. He thought I should have a pair of blue jeans.

Now, I have never worn blue jeans in my life; I hate the feel and the fit of them. By the time Jim took me to one of those enormous stores with jeans reaching to the heavens (too many not put back properly and thus even less enticing), most of the world was waltzing around in denim. We spent hours and hours at that store, where I must have tried on every single pair: straight, boot-cut, cowboy, and Indian chief. I still didn’t buy them. They were too heavy, and the bulky way the button lay on my waist made me feel like a child with a protruding belly. It had taken me a long time to get comfortable in pants, but this was going too far. I didn’t buy the jeans (and to this day cannot and will not try them on).

While we walked the vast parking lot to our car, Jim, his new pair of jeans in hand, said, “Betty, everybody wears jeans.”

If that was his sales pitch, boy, did he have the wrong customer. That word “everybody” did it for me. I heard my mother’s voice: “Betty doesn’t wear what everyone else wears. If everybody wore a head scarf, Betty wore the scarf around her waist.” Jim taught me to buy insurance, save for retirement, and ask for a raise, but wear jeans? No thank you. And I abhorred him in them with equal passion. Dear God, if he didn’t look like a Boy Scout who’d outstayed his troop’s welcome.

Out of all the marvelous things he and I did together, I think my favorite was our drives to and from Clinton. By the time I hopped into the car in the midst of snarled midtown traffic on Fridays, I was wound up from building an important business all week. The completely new feeling of making sales numbers, having women rely upon me, supporting my co-workers—being vital—turned me into a nervous wreck. Stretching oneself is always stressful.

From the moment that car door shut until I opened it again in Clinton, I never stopped complaining. No matter what I said, though, Jim always helped me through, and by the time we got there, I was okay. He patiently listened to everything from pet

ty squabbles to deep-seated fears. (Jim hardly ever lost his temper, but when he blew, I thought of the red hair of his youth.) He had a very good head on him and let me use him as the most solid sounding board anyone could ask for. I had finally found someone I could talk to.

Cristina described me as “wise out of the womb.” I’m not sure my poor Jim, a prison to my ranting as we sat in bumper-to-bumper traffic, would have agreed. But I took on the mantle of Solomon at Solutions, where my ladies dropped by for advice that stretched way past the realm of shopping. Perched on the little love seat in my office, they asked about everything from coping with divorce to finding a good orthodontist. Coming to see me became an event.

I’m going to a dinner party tonight—should I send flowers?

I have a friend who needs a good divorce lawyer. Do you know anyone in Waukesha, Wisconsin?

Why do I have to put rubber soles on my ballet flats?

How do I get a grease spot out of French lace?

Do you believe my housekeeper doesn’t iron?

Who’s the best invisible weaver in town?

How do you feel about after-school playgroups?

They imbued me with remarkable powers: tentacles that reached all over the country, eyes in the back of my head, infallible resources, and superlative taste. I researched storage out of the city to house clothes for one of my clients who had so many possessions she didn’t want to part with, and I negotiated the rate for her. I helped women line old pocketbooks, fix chipped china, or find a glass banana boat. I kept a life in my personal book with recommendations for the best wedding-dress atelier (Mark Ingram, who’d once worked at BG), shoemaker, dry cleaners, ad infinitum. I don’t know how often my own dear dentist was called on for an emergency toothache or a broken something-or-other. Requests for restaurant recommendations were so frequent that it was like a second job.

I like to make myself useful and therefore built a strong network of resources. Finding a resolution for problems involving the unknown, the difficult, and the rare was more gratifying to me than selling the costliest dress or handbag. Information, which women carried with them out of my office and far beyond, was power. I wanted to give my ladies fortitude in all things, and in that they felt better for just having asked. Like lighting a candle in church, coming to see me was a ritual of comfort.

CHAPTER

* * *

* * *

Seven

I was aghast by what I found when I opened the garment bag that had been returned to my office—wire hangers.

Nothing in the store—or my closet—not even a cotton brassiere, hung on a wire hanger, those slippery harbingers of misshapen garments. I knew that the clothes, returned as if new, were used. A few weeks earlier, I had walked a wardrobe stylist for a photo shoot through the store to find clothes—a very new area of my business, servicing theatrical people.

Costume designers, an unknown entity to me when I began Studio Services as part of my department, needed a way to borrow clothes for a play, a movie, or an Estée Lauder advertisement—and return the pieces that didn’t work. This was as novel to the store as it was to me. Loaning clothes was very scary, because one doesn’t want them coming back with stains, or pins, or having been used. There is, unfortunately, a lot of sneakiness around clothes. (I once had a very devious private client who tore the buttons off a Chanel suit delivered to her home and called me to claim that the suit hadn’t come with buttons—as if I would ever send a garment that wasn’t in perfect shape, let alone without buttons! I pictured her having the extra buttons sewn onto a sweater in some kind of twofer.) Just to get the clothes out of the store, we had to go through security, credit ratings, everything short of asking for birth certificates.

The clothes from that early photo shoot came back on wire hangers, which told me they had been cleaned. It was a dead giveaway. All I was missing was the dry cleaner’s ticket. Wear-it-and-return was not a game I was interested in playing.

Although this was my first time in this game, I’d been on the playground for some time now and knew exactly how to handle the situation. I picked up the phone and put the fear of death into the stylist.

“You didn’t use a very good cleaner,” I said.

My office has always been known for establishing boundaries. I live in strict adherence to procedure and protocol and expect those in my orbit, no matter how briefly, to do the same. I came up with the plan of charging a fee of 15 percent, which was unheard of. That way if no clothes were kept from the pull, there was still a charge. I quickly established a reputation for being very tough, which was fine by me. I’m extremely particular about whom I work with and would rather turn a stylist down if something about it doesn’t sit right with me. The wire hangers were an early lesson in that!

There were so many productions with big budgets, big-name actors, and big wardrobe budgets filming in New York in the eighties that I didn’t have to worry about losing a few shifty stylists to my forthright manner. I suspect that some of them did stay away because of it, but then I was better off without them. Studio Services attracted the best in the business just as it became a very large and previously untapped source of revenue for the store.

The production designer Santo Loquasto and his costume designer, Jeffrey Kurland, were certainly counted among those at the top of their fields. I first met them in 1980 when they arrived in search of a high-end look for Lauren Bacall in a film called The Fan. For the thriller, in which Ms. Bacall played a glamorous star of stage and screen with a violent stalker, we went in for very extravagant clothes: Armani, Claude Montana, Chanel. The movie was a critical flop, but Jeffrey, Santo, and I, who share a love of beautiful fabrics and a wit that burns like acid, became family immediately.

Over the next fifteen years, Jeffrey and I shopped for some twenty-odd movies together. They included the films of Woody Allen, such as Hannah and Her Sisters, Crimes and Misdemeanors, and Mighty Aphrodite, none of which required clothes from the store. Unlike with my regular clients, who came to me for constant feedback, I didn’t interfere when costume designers like Jeffrey were pulling clothes until I understood that my opinion was needed. Then I didn’t hesitate to offer it.

I was prepared to do whatever I could to help Jeffrey when one afternoon he ran into my office in a full-blown panic. He was working on Alice, Woody Allen’s film about an Upper East Side mother of two who spends her days shopping (familiar story line), for which we had pillaged the uniforms of the upper class (again Armani, Valentino, and Chanel—a lot of Chanel). As Jeffrey stood before my desk, it all came pouring out: They were shooting the scene where Alice, played by Mia Farrow, follows two gossips into the Ralph Lauren store on Seventy-second and Madison. Jeffrey dressed one of the gossipy friends, played by the veteran character actress Robin Bartlett, in a Beacon coat made from antique blankets and trimmed in burgundy fox by Ben Kahn, which at that time was the oldest existing American fur house.

“Sounds divine,” I said. “Very à la Southwest. Perfect for Mr. Lauren’s shop.”

“The coat is good. I’m not happy with the jewelry,” he said. “I have a silver bolo tie and some earrings, but they’re getting lost. Betty, I need jewelry.”

“Sit down,” I said, worried the poor thing was about to have a heart attack. “Do you want to eat something?”

I always fed people, both at home and in the office, but in times of trouble I found it particularly important.

“No, no,” he said. “We are literally in the middle of the scene. I just hopped into a cab and raced over here. I’m desperate!”

Now, this was a fashion emergency. I had to help him, and quick. I just hoped I had the remedy.

“What kind of thing are you looking for?”

“Something turquoise. Chunky. I don’t know. Something like what you’re wearing.” Jeffrey was pointing at the chunky turquoise, silver, and beaded Indian jewelry I had on.

W

ell, that was easy enough. I took the ring and the bracelets off my arm and handed them over. “You don’t have time to go looking. Take these and go. Get out of here and shoot!”

Usually my most important offering to costume designers was not the clothes off my back but my knowledge of the store’s merchandise. At that time Manhattan department and specialty stores didn’t have studio services. Other than me, Connie Buck at Saks Fifth Avenue was the only one. (My interaction with Connie was very limited. I first encountered her when we both attended a costume designer’s surprise birthday party. I went up to her and put my hand out to introduce myself—when you’ve had enough therapy, you put your hand out to everybody. She, however, didn’t move a muscle.) It wasn’t until a decade later, in the nineties, that other stores like Barneys and Henri Bendel started their own departments.

Naturally, costume designers shopped all over the city. But when they came to Bergdorf, carrying pictures and sizes on paper from which to pull multiple looks, they used me like a personal computer. The inventory was stored in my brain, and, better than a computer, I actually knew where the clothing lived. I guided Albert Wolsky to the white dressing gowns he envisioned for Meryl Streep in Sophie’s Choice and Jeffrey to a less expensive version of the silk blouses he wanted for Mia Farrow in Broadway Danny Rose.

The people I worked with were very hands-on. Designers walked the entire store with me and dove into the stockrooms. They felt very privileged for having the opportunity to enter the store’s back rooms and the chance to discover some tucked-away clothes not on the selling floor. They think you’re giving them a gift, something special seeing it all hanging in depth. How many times did I hear, “Have you had this on anyone, Betty?” (Today I realize this is against the store’s security rules; you aren’t supposed to bring anyone who doesn’t work for the store into the back rooms because management is worried about people stealing the merchandise. They let me do it because I have a good, long record.)

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist