- Home

- Betty Halbreich

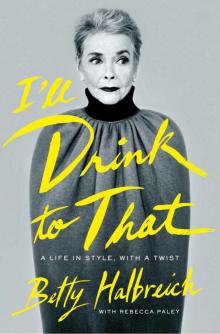

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist Page 16

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist Read online

Page 16

Compared to the psychological dance I did with my private clients, assisting professionals was a cakewalk. There was just as much troubleshooting to be done, but our rapport was full of the lightness of direct shoptalk.

“The actress will look good in this,” a young designer said, holding up a dress.

“No way. That dress doesn’t fit anybody.”

“But I love the color.”

“You don’t wear color. You wear a dress.”

I had the huge pleasure of knowing John Boxer, whom I met while he was working on Raging Bull. I was struck by how John achieved the iconic 1940s look that Martin Scorsese wanted by putting the lead actress, Cathy Moriarty, in playsuits and peasant dresses that could have come right out of my closet as a younger woman. But my favorite touch of all was a marvelous white crocheted snood he put on the actress’s head, which I believe brought the headpiece back out of retirement for a period.

One evening John made an appointment to bring in the director Alan Pakula and the actress Candice Bergen, who were working on the 1979 film Starting Over. The fitting room was laden with gorgeous Candice clothes that John and I had spent the better part of the day gathering. We had everything down to the shoes for her character as the songwriter wife of Burt Reynolds.

The clothes went just fine on Candice, who could have worn a paper bag and looked absolutely stunning. But when we got to the shoes, an elegant pair of heels, she had a difficult time walking. She looked as stiff and scared on three-inch heels as if someone had just put her on stilts.

“I’ve been on horses most of my life,” she said, shrugging apologetically.

Having grown up in Beverly Hills, the daughter of a famous ventriloquist, Candice, more brain than bombshell, had the luxury of circumventing the conventions of life she found boring—like wearing heels—until now.

“Somebody here in this store is going to have to teach this woman how to walk in shoes,” Mr. Pakula said.

While he sat outside the office as if it were a stage or a runway, Candice, arresting in head-to-toe beige (including the heels) was hesitant to try the shoes on. John and I prodded her into taking the plunge, and she made it.

Months later Candice brought her beautiful mother, Frances Bergen, in to meet me. Frances, who had been a Powers model and was as gracious as she was extraordinary looking, wasn’t the only relative Candice brought to my office. I also got a surprise visit from a tiny thing all bundled up shortly after the birth of Candice’s daughter, Chloe. Although we don’t work together much anymore, we have a warm relationship. Candice will call out of the blue to ask if I saw such-and-such blouse from the catalog and would she like it. I give her a quick no, and we go on to talk about real life.

Remembering real life was the key to what many called my talent in dealing with celebrities. I have never been awed by actors coming to the office. They’re human beings, made up of the same matter as the rest of us mortals. I do not fawn over them; it would make me uncomfortable and, I believe, them as well. Instead I like to divert them while we’re doing the fitting, just as I do with my private clients.

As Meryl Streep and I waited for a fitter to alter a dress for an awards ceremony, we talked about the loves of her life: her children. She told me how she liked to sew and was making Halloween costumes. How exciting it was for me to hear that. It was much easier to talk about real life—and not playacting life.

When the talented costume designer Albert Wolsky brought in Angela Lansbury, with whom he’d worked with on The Manchurian Candidate, we nattered on about Ireland—where she had a home and Jim and I very much wished we did—trying on clothes all the time. I served a lunch that included fruit and wine on the white tissue paper I always laid out under plates in lieu of linen. We did get a lot done, and, more important, everyone was comfortable. (She just returned this past year after all that time for two outfits for a trip to Australia and an appearance on Channel 13. This time the entire fitting took only an hour.)

Before working on any of Woody Allen’s films, I met Mia Farrow when she came in with Jane Greenwood, a cheerful and knowledgeable costume designer and a favorite of mine. We found a very simple Adele Simpson print shirtwaist dress, price $125, for a play the young actress was starring in with Frank Langella. Mia put it on and, turning to us both, exclaimed, “Do you know how many meals this would buy for the children in Biafra?” No, I didn’t. At the time I didn’t even know where Biafra was.

Jane also brought in Liza Minnelli for Arthur, who sniffled through the entire fitting. Although when I said to her, “Your cold sounds very bad. You should not be here today,” she just looked at me strangely and huddled in the corner of the dressing room.

Stockard Channing came with William Ivey Long, a costume designer I was introduced to when he was fresh out of Yale by my young assistant and fellow alum Maren (who every day brought to work her lunch of a white-bread sandwich in a Wonder Bread wrapper). When we met, William appeared in a navy blazer, white shirt, striped tie, khaki pants (and to this day wears the same outfit). The John Guare play Six Degrees of Separation was my first time working with William, and before I knew it, we were fitting Stockard on top of my desk. I suspect it gave William a better perspective on the short actress.

Dressing actresses for real life was as easy as for a movie or a play in that they were used to looking at themselves with the objectivity of their profession and having a committee weigh in on their image. (Although in one way celebrities are no different from my private clients in their distortion of reality: They usually downsize themselves, too.) When the young, gutsy, and small Stockard came back later for her own clothes, I taught her how to show off her beautiful and shapely legs by putting her in short skirts and high heels. I had to elevate her in stature. Shoes can do that, even if they’re modest heels and not the stilts that women are wearing today.

Great style, of course, has less to do with physical beauty than with high intellect. Joan Rivers, who for many years has come to the Solutions department, reinvents herself season to season, which only someone with great intellect can do. She is the definition of multifaceted, moving from QVC to a nightclub in Minneapolis to a program with her daughter at the 92nd Street Y, with the style of her clothes hinging on the gig of the moment. Although her onstage routine is filled with self-deprecating jokes about her appearance, she is a person who truly knows what looks best on her. Joan understands what fits and she knows what feats the right alterations can accomplish. And Joan isn’t above suffering for style. I once watched her have a skirt taken in so much that she wasn’t able to take strides more than a few inches long. It was, however, slimming and made her feel ten feet taller.

She is a chameleon, and not just with fashion. When I went to see her act at a small club downtown, right before she went up onstage, she looked as if she’d been out all night. The next moment, with the lights on her and the people at the cabaret tables roaring, she looked like she’d taken a rest cure. Joan feeds from her audience, which includes not just those who come to see her in a club but also people on the street.

Behind a closed door, she’s as human as any person I know. Through countless fittings, we have talked about our families, our lives with men, people we’ve lost. It’s a wonder how we ever got any clothes on her and fitted! The woman on TV’s Fashion Police is not what one gets in real life. Sensitive and still remembering her past, Joan is generous to a fault. The fitters love and admire her, particularly Jeanne, who was truly dedicated. No matter the weather, sleet or snow, Jeanne rode the bus in from New Jersey every day of her life and wore out the chair in my office waiting for clients. She, who like me regarded rising to challenges as the hallmark of true service, rarely if ever said no—and Joan appreciated her for it. One Christmas the store hosted an appearance by Santa Claus, and Joan brought her young grandson in to meet him. Just as they were about to get their photo taken with Santa, Jeanne passed by. Joan pulled the fitter int

o the picture for a true Christmas family portrait.

Studio Services came to represent about half of my total sales for the store—and not because of my times spent with celebrities. The success of the theatrical aspect of my business was due in great part to the clothes feeding frenzy that was the soap-opera industry of the eighties.

Before the late seventies, when soap operas became breadwinners for the network, costume designers for the daytime programs were on limited budgets and mainly procured their wardrobes from large department stores like Abraham & Straus, which lent clothes to the programs, took them back, dry-cleaned them, then sold them to real people.

By the time those designers were coming to me, soaps were king. With big costume budgets, they used up clothes like Kleenex—though they certainly didn’t purchase their entire wardrobe from me (no budget is that big). They were clever shoppers who used the entire city to clothe their characters. Carol Luiken, the costume designer on All My Children for twenty years, bought men’s suits at an Upper West Side store called Foward that carried merchandise from bankrupt stores and factory rejects. A seedy store off Times Square, which sold electronics in addition to women’s clothing, was perfect for the show’s hookers. Carol—like Don Sheffield for One Life to Live and Bob Anton for Search for Tomorrow and Guiding Light—came to me for the female characters who were truly dressed in the latest fashions.

With dozens of cast members (not to mention extras) on television 260 days a year, there were a lot of costumes to create. The store’s lingerie department got quite a workout, thanks to the many scenes set in the bedroom. The need for satin robes, provocative nightgowns, and lacy camisoles was insatiable. The costume designers used that department the way most people use a grocery store.

Shopping for soaps, we were defining the style of characters with five-, ten-, even twenty-year life spans (and often the characters were followed just as much for their clothes as for their story lines). While looking at dresses, we discussed them as if they were alive. What did this person do? Whom does she dress for? What does she think about clothes? In a funny crossover between my work with private clients and theatrical ones, I was creating costumes that were real wardrobes. Indeed, the costume designers established a physical closet in the studio for each character, filled with dresses, suits, purses, shoes, and—in the days when people still wore them—hats. (Once when he needed a cocktail hat for a particular scene, Bob Anton and I went to the counter of the hat department on the first floor, where he proceeded to try on the most lavish chapeaus in the store. Before you knew it, we had a very large group of people staring at this man with black curly hair and a bow tie adjusting women’s hats on his head. Bob was completely oblivious to the crowd as he busily fussed with the veils.)

I spent so many years shopping for those characters that I got to know them as well as any client. Erica Kane, All My Children’s seductive powerhouse played by the gracious and gentle-spoken Susan Lucci, was the perfect Solutions customer. By turns a high-fashion model, a cosmetics tycoon, and a magazine publisher rolled into a perfect figure that made clothes so easy, Erica was truly fun to dress. Before she arrived at the store, the dressing room was prepared like a closet full of the most petite and glorious clothes. The newer foreign imports that many women found hard to understand were a cinch on her.

Carol Luiken—who could sew using a pattern and had a uniquely intellectual interest in period pieces—usually arrived to shop a little earlier than the store’s official opening so that we could get a head start before the customers filled the floors. I dutifully took her to her favorite places—for Erica she favored the bright drama of Valentino and Ungaro—but I also steered her in different directions. (Even professionals benefit from a push down a new path every now and then.)

I have never favored a particular designer or label but rather go where my eye draws me. (Indeed, when I first arrived at Bergdorf Goodman, people shopped the store, not designers. Customers looked at scarves, cashmere, hats, and furs—not names on labels.) No one designer is consistently good. Some seasons a particular designer can be terrific, while the next he or she can be dreadful. Lines in themselves are not usually monolithic either but vary from piece to piece. That’s why I stay flexible in my thinking and never write off anybody after a bad collection or slavishly follow someone after a beautiful season.

While introducing new ideas to clients or costume designers, I play the seductress, caressing the fabrics to illustrate their appealing feel and moving the clothes around so they are more alluring than a limp garment hanging from a rack. During one particularly good season of Christian Lacroix’s, I suggested it to Carol for Erica.

“I don’t know,” she said. “His clothes are fussier than I’m used to.”

I can be accused of many things, but fussy dressing is not one of them. Carol dutifully followed me; we had known each other long and well enough that she could trust that I wouldn’t take her on a fool’s errand. Once inside the department, I separated out the jackets, skirts, and pants, pairing them with basics that at once highlighted what was best about the look while also creating a simpler version of it.

“Why, Betty!” Carol exclaimed. “They said nothing to me until you touched them. What kind of magic do you have in your hands?”

There was no magic; I knew my merchandise from hours of poring through it every single day. I also understood the references these costume designers used while imagining their characters. When Carol was creating the look of a new character, she said, “I envision her as a Diana Vreeland type.”

That is when my head kicks in and my memory bank spews out areas of clothes that aren’t always visible.

I showed her a spare, collarless kimono jacket and a palazzo pant from a line of simply cut clothes. “Yes!” Carol said, eventually pairing the clothes she bought from me with ethnic jewelry inspired by the cuffs and other large costume pieces worn by the legendary fashion editor.

Usually my work on the soaps was less about esoteric creative concepts and more about making sure there were clothes on the actors’ backs by the time the cameras rolled. More often than not, the costume designers came in with impossible needs. I heard “I’ve got a terrible problem, Betty” so many times that it could have been my middle name. I seemed to become the troubleshooter who got them out of jams such as needing three of the exact same outfit but in three different sizes for a scene shooting the following day in which a man is romancing one woman while he fantasizes about another in the same scenario (and the third was for the stand-in).

The insurmountable also involved finite resources. Everyone has a budget, and I always recognized the importance of that fact. Whether it’s a woman coming to me for clothes for a cruise or a costume designer staging a Broadway play, I politely ask the price range and happily work within it. I have found that my respect of people’s pocketbooks is appreciated, even if it means they don’t find anything in the store. I’ve been known to refer them to another store—unthinkable to most in my business—where they would be more comfortable financially. To be embarrassed over the money situation is not in my realm of things to be.

Studio Services was no doubt hard work, but I found it incredibly stimulating. It was fun walking the store with these designers. They were college grads from Yale, Columbia, and other fine universities, and they opened my eyes to a wholly new aspect of fashion. While design and fit came naturally to me, I learned a lot about how clothes change onstage or behind the camera. Highly saturated colors bleed on-screen but work well onstage. Stripes, checks, herringbone, or any small, intricate patterns vibrate on television in what is known as moire patterns.

The technical aspects of wardrobe were easy enough for me, but there are philosophical ones, too. The designer hopes to bring something natural to the picture. The audience should not always be looking at the clothes—there is a story involved. One of the more interesting aspects of shopping for costumes was that most of the time

it wasn’t about hunting for pretty clothes. Yes, designers came to me for my taste and knowledge of the store. But building a character, even through clothes, is complex. The ones where some life truly comes through inevitably include humor—which I always try to bring when working with my favorite costume designers.

Not everyone, however, found me so funny. When the boutique owner, costume designer, and force of nature that is Patricia Field first came to see me in the nineties as she was starting on the wardrobe for Sex and the City, she arrived with conflicting reports about my humor—or lack thereof. One of the stylists from her clan had complained, “That Betty is so mean. She just won’t give me the time of day.” Yet simultaneously a designer who worked with her said, “That Betty, she is such a riot. I just love going over to see her. She makes shopping fun.”

Was I a snob rejecting anyone who didn’t look the role? Or someone who only relates to avant-garde types? Pat had to meet me to find out.

When she walked in for her appointment, she stood in stark contrast to the muted tones of my office’s decor. Her Ronald McDonald–red hair (that matched her shade of lipstick) was capped by a crazy hat decorated with all kinds of slogans. A thin, mutilated T-shirt revealed a pair of lacy bra straps and her startling décolletage. The nails on her right hand were painted a deep purple, on her left a clear shimmer. Even I had to admit that the way she pulled herself together worked, though I couldn’t have described how, exactly.

In her raspy smoker’s voice, Pat talked to me about the four distinct women around which this new HBO show about being single in the big city revolved. The look, she said, was crucial. The style would have to be nuanced and not just another group of girls in miniskirts and high heels. This was a show for women, about women—and women care about style. Based on her description, I thought we would start on the fourth floor where there was one department I wanted her to see. Unfortunately, there was a lot of bad between the elevator and my destination.

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist