- Home

- Betty Halbreich

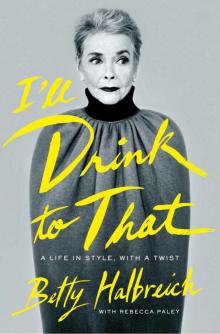

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist Page 17

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist Read online

Page 17

“Who bought this garbage?” I said.

I hadn’t even realized that my inner thoughts had escaped through my mouth until Pat and the two heavily tattooed assistants she’d brought with her started laughing. I guess they didn’t think anyone in this store would be gauche enough to speak the truth—in their language, no less. I simply cocked an eyebrow and kept walking.

“Now I get what I’m dealing with,” Pat said, sizing me up admiringly. “You’re an archcritic.

“You,” she continued, aiming a purple pointer nail at me, “are someone who needs to be amused. Like all creative types. Like me. I can see why it doesn’t work out with you and everyone. We veer toward the people we think are going to give us the birdseed.”

It was, as they say, the beginning of a beautiful relationship. From the outside you couldn’t have found two more different people. She was a downtown party girl whose House of Field clothing line appealed to drag queens. I, an Upper East Sider, cloistered myself in the store during the week and in the quiet of the country on the weekends. But you can’t tell a book by its cover. Pat was right: We were alike, and in more ways than just enjoying a good wisecrack.

Despite her bizarre appearance—and social life—Pat is extremely disciplined, as evidenced by the group she brings with her on shopping trips. Everybody who’s come out of her barn has done well. (Today I work regularly with her protégés, such as Gossip Girl’s Eric Daman, Smash’s Paolo Nieddu, Jackie Demeterio of The Big C and the film The Other Woman, and Sue Gandy, who has been with Pat so long she can read her boss’s mind.) It doesn’t matter how many tattoos or piercings they have, they say “please” and “thank you,” which is quite extraordinary in this business. Pat also doesn’t resort to resting on labels but, like me, is guided by her taste. The style of Sex and the City was revolutionary precisely because it paired high-couture items with things one could buy on Canal Street. Whereas on any other program before then, the classic Chanel jacket would signify high society, Pat changed its function into that of a jean jacket to go with a pair of Levi’s and a ribbed white tank top.

It was exciting shopping for Sex and the City (although I must admit to never having seen the actual show: I don’t have HBO). Pat never came alone; her group was paired off in twos—Eric and Paolo, Sue with Pat. We had the best time with clothes. It was like playing with dolls, because that’s how the characters dressed. They were conjured up in the toy box of Pat’s mind, where style meant an abundance of riches. If I thought I’d seen over-the-top, Pat went over over-the-top—and then some. She mixed prints as if she were blind, pairing a white skirt with bold black leaf shapes and a coat dotted with pink starfish. If we found a great dress, she found something to go over the great dress—and then something in the hand, around the neck, on top of the head. She flung a navy vintage nurse-style cape over a white button-down that went over an orange bustier. There was so much stuff-upon-stuff, and then whatever she bought she embellished in her workshop with even more. I doubt that a designer would have recognized his or her own creation when it appeared on the show.

This plethora of clothing took herculean shopping trips, for which Pat was more than willing and able. When we were on the floor, I always rued the fact that I didn’t have a harness to tether her to us. She was in one spot pondering a pair of cuffed pants, then in another diving into a rack of silk blouses. We lost her more than once in the sweater section. The clothes she pulled heaped higher and higher in my arms until she got stuck on something—did this designer run small or true to size? Then the next thing you knew, she was trying the clothes on. Once she was so engrossed that she misplaced her own clothes in the store! Her two assistants and I had to retrace our steps until we found Pat’s things lying forgotten on a chair.

I didn’t mind the maniacal adventures with Pat. On the contrary, I found in them a release. Her big personality and fearless creativity were entertaining and an inspiration.

Entertainment was always walking through my door in the form of designers, who in years past came to the store for a day of meeting buyers and customers, then to my office, where we smoked and laughed and smoked. Those were marvelous times. (And, in hindsight, the most creative: We were going into a whole new, more relaxed, more provocative, and less luxurious look.)

I don’t stick myself in front of the designers when they appear for trunk shows. I don’t care for viewing clothes that way. They romance and dance around the collection, trying to whet your appetite to sell it, so I’m very scarce on those mornings. I like to hear the click of the hangers as I’m looking at the clothes for myself. However, when Isaac Mizrahi had his first trunk show at the store in 1987, I got very involved. I adored his clothes—American, colorful, well fitting—and I adored him. The lovably intellectual twenty-six-year-old, blessed with an unbelievable memory bank, spent most of the day in my office getting an education.

Many designers understand what it means to listen to their instincts, follow their muse, and make beautiful clothes. My contribution is that I can look at someone’s work and say exactly who the customer is. Then out of all the people who come through my office, I shepherd the clothes to the right ones. Isaac described what I do not as selling clothes but rather placing them. “It’s almost like an adoption agency,” he said.

I introduced Isaac’s clothes to Candice Bergen, who looked perfect in the crisp lines and bold hues. Jane Pauley bought a raincoat, and a week later Liza Minnelli took a beautiful piqué coat. I called to inform him of all the purchases, because I knew he would be thrilled with the news—and he was. Back then, before the big-time marketing and hoopla that now accompanies a high-end clothing line, designers weren’t the stars they are today. Finding out that an icon like Ms. Minnelli was wearing one of his pieces gave Isaac, just starting out, a much-needed boost.

I’ve had the marvelous luck to cull from and sell the unknown before everyone else jumps on the bandwagon. (I like the challenge within my own head.) Knowing the person who made the sketches, picked out the fabric, did fittings, and delivered a line makes me feel closer to the clothes—like meeting a long-lost relative. This was true of Isaac, as well as Michael Kors, first discovered by Dawn Mello. The Bergdorf Goodman executive spotted the designer while he was adjusting pieces he had designed in the window display of Lothar’s, a store across the street on Fifty-seventh that sold trendy low-end items such as tie-dyed corduroy leisure suits to a high-end clientele. Within a year he was selling his own line at the store and gathering a coterie of people whenever he appeared. He was a true showman, and customers and salespeople alike flocked to him. It wasn’t a shock to find out he’d been a child actor.

No matter how popular they became, Michael and Isaac never visited the store without stopping by my department—they didn’t dare. They oohed and aahed, kissed and smoked with every human being who happened to be sitting there. (I like to find out what other interests designers have; most are very good at things other than designing. To create vibrant clothes, one must be multifaceted, a big reader, conversant in art, or otherwise inspired.) The visits were due in part to the fact that they knew that on my love seat they would have a good time (and be fed). But I also provided them—as well as many others starting out or trying to stay afloat in the industry—a unique perspective on fashion.

With my finger on the pulse of what women want, I communicate the practical application of a designer’s invention. I can tell established designers when they are cutting their armholes too small for regular women or that the necklines of their latest collection do nothing to flatter a bosom. Consider it my contribution to the feminist movement.

The one battle we’ve all lost is the battle of the sleeve. For some godforsaken reason, designers today refuse to give the option of a sleeve—and women, as a rule, do not like their upper arms. You can work out from now to kingdom come (or so I hear), and the arms are either too muscular or too flabby. So give the option of a cover, I say. You can always

alter the fabric of a sleeve—shorten to your liking or let the fabric down. But give an option. Today the designers feel the no-sleeve look is younger. Nonsense—it has nothing to do with age. No one else will take the step for a dumb sleeve!

Pants are another real doozy when it comes to fit. When Isaac started out, he made pants that fit extremely well. (Great-fitting pants are rarer than diamonds.) I put all my clients in them, and everyone felt wonderful. That is, until one day they suddenly lost their magic. Oh, no, no, no! I wasn’t going to lose these gems without a fight. The next time we spoke, I gave it to him straight. “I don’t know what happened, but your pants no longer fit anyone,” I said. He was polite but defensive in his response.

I know I risked his not liking me. Isaac was on a roll; everybody loved him. Designers cultivate fit, so a critique like mine was devastating. Nobody else would call out a misstep to a fashion darling like him. The problem could have been anything from a different fit model to manufacturer. Figuring it out wouldn’t be easy.

But he did. Isaac’s pants returned to their former glory, and he thanked me for the help—in his own particular way. “It is like your mother telling you you need to lose a few pounds,” he said of my criticism. “It’s annoying, but it’s true, and it helps.”

I found that many young people sought out my truthful assessment of their work. William Ivey Long in his blue blazer and tie brought in the wonderful writer Wendy Wasserstein and sketches of the most extraordinary lingerie. He and the playwright planned to manufacture the lovely kind of lingerie that one found in films. Unfortunately, she was already ill and passed away before they could make a go of it. Word of mouth brings jewelry, handbag, and clothing designers; I do not turn anyone away. Rather than give them hope when I know there is none, I’m brutally honest. When I make a recommendation, however, the store reacts and will see the person, which is worth a great deal to any artisan.

Many designers over the years have taken my direction, with one notable exception. Mr. Beene, for whom I developed a deep affection, never would. He didn’t take direction. Period.

A year or so after our awful parting of the ways, Mr. Beene reconnected the thread between us by contacting my office. Immediately I knew the voice of his secretary, Joyce (who still works for the Beene industry). “Mr. Beene would like to have a cup of coffee with you tomorrow morning,” she said.

I exorcised the fear and anger I had felt over the vicious note he hung from my office door and accepted. Anyone who does something like that, I reasoned, is very unsure of himself and lonely.

Our coffee date was delightful, even though he was the most discontented human being. Mr. Beene wanted to know about everything going on at the store—who was doing this and who that. As that first date turned into many over the years, I became his confidante, at least in the commercial aspect of his life. We gossiped about the store and his studio, but our past life together was never mentioned. That was fine by me, because I was here and secure. Mr. Beene didn’t have the power to take away my safe harbor. I even felt flattered that the two of us had become true friends.

I went on to sell a lot of his clothes. Indeed, he became one of my favorite sources. Even Mr. Beene, however, had his good seasons and his bad. But I couldn’t tell him to push a seam, lift a collar, or turn a bow. He wasn’t good at evening clothes, although he didn’t know it. His conviction in his product was unflappable. How he designed a piece was how it stood.

I didn’t begrudge him his confidence. His suits, jackets, and less formal dresses were exquisite. The people I dressed in his clothes still own and wear them. Recently a client walked into my office wearing a Geoffrey Beene double-faced wool jacket with one fastening at the neck that was at once easy and architecturally masterful. The fabric, deep green plaid and cocoonlike, is of a quality that simply doesn’t exist anymore. Her jacket was probably at least twenty years old.

I, too, wore his clothes. Every Christmas he generously sent me one of his samples, which couldn’t be reproduced for one reason or another and had thrown his head of production into a fit of pique. I treasured my beige wool-and-cashmere seven-eighths coat and my green plaid jacket, because I understood just how rare they were.

Apparently so did Mr. Beene, who later on asked to have all the sample clothes he’d given me over the years for the archive he was building. Like a dope I agreed, and consequently most of my Beene clothes are in that archive. The man was a one-of-a-kind eccentric. Upon the publication of my first book, Secrets of a Fashion Therapist, in 1998, he loaned me a taupe taffeta dress to wear to a grand party given for me in a glorious apartment. I loved that Beene dress. Its narrow sleeves that went to the wrists, its trapeze shape, and its beautiful stand-up collar were to die for. I shall never forget it. But, like Cinderella, I had to return it the following day. If I could do it all over again, I would have fought for that dress.

I have the sneaky feeling that Mr. Beene, never Geoffrey, is up there aware of everything being written about him. He truly left his mark on my life—be that what it may. Sitting on my desk, right up there with my children’s, I have a photo of one of our last visits together.

CHAPTER

* * *

* * *

Eight

Mr. Cronkite arrived at my office looking every bit as natty as usual—in his uniform of a navy blazer, a beautiful custom-made shirt, and a striped tie—but his expression was uncharacteristically unsure. Walter Cronkite’s wife, Betsy, a client of mine for a long time, had taken very sick very suddenly.

The legendary newsman would come in every Christmas for her (he picked out a lovely tailored outfit for their boat trips or a cocktail dress for their busy social calendar). Meanwhile Betsy did the gifts for their girls, Nancy and Kathy. The pair, who shared a solid marriage for sixty-five years, couldn’t have been more different in appearance. He was beyond immaculate, and she was like an old shoe!

I adored the way her Christmas lists were presented over the years, usually on the back of a long, narrow Con Ed or bank envelope. We ordered cappuccino for her and joked about how women adored Mr. Cronkite. Betsy pointed out how all the ladies at his book signings seemed to speak with a southern accent. Then it was down to work.

Her children were the main thrust. Treats for the girls always came first, and Betsy came next, if at all. She was the glue who held the family together. Clothes were the least important thing in her life; they were nothing but a necessity. She cared more about a funny old cat they had who was fed with chopsticks by a Chinese retainer. I always said to Mrs. Cronkite, “You should write a book on the family.” She had the letters she and her husband had sent to each other during World War II, when they were both war correspondents.

Betsy didn’t give a nickel for day dressing. However, she had to play the part of Mrs. Cronkite in the evening. She would bring me the Adolfos she’d had for centuries, and we would alter them, get them up-to-date—if possible. She poked fun at the cocktail-party circuit until we eventually found a dress. When I saw the end result, pictures of her in the paper “all done up,” I smiled to myself, thinking of the person in the dressing room.

Now that she was ill, Mr. Cronkite took out the list of gifts for the girls, one that, instead of being scrawled on the back of a Con Ed bill, was neatly written on card-stock stationery. The contrast came as a jolt to my system.

I brought the selections to him and his protective longtime secretary, whom he had brought along. (It’s a waste of time to cart people through the store; they only end up bewildered.) He had extremely fine taste, so we gave short shrift to the looking part. He would choose, ask my advice, and among the three of us we put together beautiful Christmas packages.

When it was time for him to go, I rode the elevator with him down to his car. As we approached the exit door, he turned to me and in his most recognizable, beautiful voice, said, “What will I do without Betsy?”

They had been married for more than hal

f a century; his fear and sadness were not only palpable but also understandable.

“Mr. Cronkite,” I said, “you will be pot-roasted to death.”

When someone crosses my office threshold, I take in the whole person and not just the items on the shopping list. I dive into the problems of day-to-day living, which include dealing with birthday gifts for a new daughter-in-law and suitable clothing for sad occasions such as funerals.

With each of my long-standing clients, I had first entered the dressing room a stranger. But after years of putting on and taking clothes off of women’s bodies—as they grew bigger with children, aged, lost weight after divorces, or were ravaged by illness—I became a confidante and sometimes like family.

In the simple act of disrobing, a woman bares her soul, and I am there as a witness. Stripped of her clothes, she is very exposed. It is my job to make her comfortable with me and ultimately with herself. Although I’m not used to it, on occasion I have been locked out of the fitting room. I keep knocking on the door until finally I get one foot in. “Now, look,” I say. “It’s much easier if I’m here to zip you up, unzip you, and try the clothes on.” Usually that works, and embarrassment gives way to an encouraging intimacy.

I have never taken advantage of this vulnerability in order to sell clothes. (I have one client who tries her clothes on with her back to the mirror, facing me. Trusting and preferring my opinion over her own reflection.) Rather I honor it by being a good listener, which I consider the most important attribute I bring to my work.

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist