- Home

- Betty Halbreich

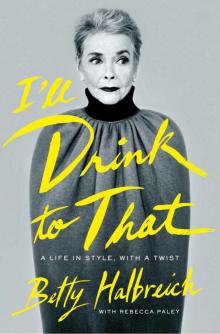

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist Page 19

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist Read online

Page 19

As we sat in that office together, she was so worried that I ended up comforting her, which was a welcome distraction from my own anxiety. The surgeon was cold and to the point: It would have to be removed, and the sooner the better.

Within the week of his terrible proclamation, I was in Mount Sinai Hospital and on the operating table. The noises surrounding me—hustling and bustling, chatter and orders—made me feel like I was in a supermarket. Then the lights went out.

I awoke to more hovering in the recovery room. As soon as I could fully open my eyes, I looked up at the nurse and said, “Take me to my family.” While I suffer so much with fear beforehand when things get very bad with me, I always muster some inner courage and find the strength to move forward. The nurse eventually did as I asked and brought me to my family, that being Kathy, John, and poor Jim, who was white as a sheet. He, too, was no great fan of hospitals. So the sight of me bandaged from neck down to rib cage must have been quite a shock. (When they left the hospital, Jim was so upset he forgot where his car was parked, and they all spent a good deal of time in Mount Sinai’s parking lot.)

I had a private room and a nurse. (In those days one could afford it.) I survived the surgery; however the night nurse, who must have been in her seventies, nearly killed me. The horror of her pulling me up to change my pillows or turn me by the hair while I was in so much pain! The next day brought yet more horror: I had an allergic reaction to the surgical tape in the form of an agonizing rash all over my upper body. The surgeon who discovered it promptly took two hands and yanked off the tape. The pain was worse than the operation. Who had time to agonize over what had been removed?

Frieda made up for the torture by taking good care of me at home. She coaxed me to eat, although I couldn’t get a spoon to my mouth because food was a turnoff. Corinne and her husband, Roger, checked in on me. All my new and old friends were considerate and kind. I did have Jim, but illness was not his strong suit. It really frightened him. Two weeks later he picked me up on Friday—back to our routine—and I was glad to rest in his small apartment with the windows open so I could hear the mourning doves at daybreak. Still, I felt alone; illness can do that.

Sonny had crept into my head while I was in the hospital. When I got the nerve to call him, however, he was cool and I felt devastated once more. His only offer was to have Prince, the chauffeur, come pick me up at the hospital and take me home.

The children were concerned, but they had their full lives. Sonny had been wrong about John, who went off to a small college, graduated in only three and a half years, bought a truck, took a dog from the pound, and headed out west. He worked in kitchens and did all sorts of odd jobs. When he came back east, he worked on a goat farm making cheese and then earned a teaching degree from the University of Massachusetts. John went on to get his master’s degree in education at Columbia at night. Would anyone believe it? How we anguish and never know what the end will be. Sharing my love of nature, farm stands, and home, John had grown into a super dad of twin girls who would give up anything for his children.

Kathy never changed from the little girl who was always her own self. Although Sonny nearly had a heart attack after walking in on her painting a nude at her Art Students League class, that didn’t end her career in the visual arts. At fifteen she was the youngest person ever accepted by Skowhegan, an artist’s colony in Maine, where she painted with adults.

Her life has been full of achievements. After her graduation from college, Kathy stayed in Bennington to work on the Bennington Banner, a fine newspaper. Then she took a job in admissions at the college for a while, which led to a job at MIT installing new galleries. During this time she met her future husband, a very Germanic lawyer from Grosse Pointe, Michigan, with quiet, piercing blue eyes, reddish hair, and a beard that was already turning white. They married and had a son, Henry.

The Walker Art Center in Minneapolis beckoned when her son was barely two, and Kathy became one of the most outstanding art directors ever. She developed a fine reputation, known for her innovativeness, good judgment, and extreme honesty. People in the art world began to turn to her, not for controversy but for the new. She gained prominence in her field without seeking the limelight. Her standing in the art world was earned not only by being intelligent but also a good listener. It is hard for me to look at photos of her in handmade smocked dresses and realize that lamb chop did not go down. She was and is some pack of her own person.

Neither she nor John had to worry about the kind of mother who worked full-time, and that’s the way I wanted it. My biggest gift to them was the freedom from worrying. When they were little, I was a crazy mother who overly bathed, overly dressed, and overly chastised them for manners. A lot of it stuck, but just as much went right down the sink. Now that they were grown up, I never nagged, “Why don’t you call me?” If I wanted to speak to one of my children, I picked up the phone and called them, as in any other adult relationship. The relationship I had with my own mother, where I had to speak to her every other day, was from a different era that I let be.

I didn’t want to encumber their lives with small talk. But when the important things arose, I knew where they were. I didn’t worry that we didn’t spend every holiday together. When we did, it was wonderful. Kathy, now the cook of the family, took over birthdays, Christmas, whatever. That is my treat. I am very proud of my children, and they’re proud of me. “We are cuckoo,” Kathy said of our family. “But we would rather be cuckoo than sane.”

And so I felt independent enough to go to my daily radiation treatments during the week alone. The doctor’s office was always filled and became like a club. I saw the same patients during the week, although, sadly, some didn’t make it over the long haul. The people who worked there were caring. In a dark room, I was painted on the right side of my chest where the very large, extremely frightening machine took aim. The radiation was meted out in small doses, and the technicians were very careful. I was quite fortunate in that I didn’t suffer burns the way many patients did. I would leave the radiation appointments on Seventy-fifth Street and walk slowly home. There wasn’t much else I could do.

I had a very difficult time facing my mirror; I felt so disfigured and so lopsided. It took me weeks to look at what they had done—a mastectomy—and then I was revolted. From then on I never looked—and dressed with my back to the mirror. To bed I wore heavy T-shirts so that Jim would never see me in that condition.

Instead of my image in the mirror, I carried inside my head the image of a woman I’d helped in the beginning of my career. I had pulled a whole wardrobe for the client, a member of a prominent American family often in the press, and was ready to zip up the first item when I turned around to find her in front of the mirror, deformed and shocking. I hadn’t been forewarned about her double mastectomy; apparently this was her way of announcing the news. The reveal was aggressive and angry, like the scars running down her chest, made all the more provoking because she was typically a guarded, private woman. Who could blame her? I kept marching forward through the awful revelation by concerning myself with how to solve the very different fit in her clothing—and make her comfortable even if she was less concerned than I believed.

I’m tough and don’t give in when it comes to most things, including my own recovery. Reconstruction was never my plan. No more hospital, thank you. I have never been a great patient. I’m terrified of everything medical—including dentistry. As I say to my dentist, whom I’ve known from the first day he came into practice, “I love you as a person, and I hate what you do for a living.” My method of preventive care is to wish things away.

My mind-set after my breast-cancer surgery was to get back to the store as quickly as I could. When I returned six weeks after my operation, management was surprised that I was back so soon. “Why are you here?” they asked. “Shouldn’t you be taking it easy—at home?”

“Why?”

Little did they know, I

needed them more than they needed me.

During the first day back at work, my footing was unsure. Everyone was delighted to see me. A dear fitter, Rose, who’d visited me in the hospital and brought me homemade cakes and cookies, was there to welcome me. (A few years later, she herself succumbed to breast cancer.) My greatest comfort, however, was my routine. I looked at my datebook, which was blessedly filled with tasks needing my sole attention.

Jane Trapnell and Susan St. James, Kate & Allie—11-ish.

Betty Buckley has an audition and needs to come in today for something to wear.

Mrs. Rockman called to invite you to a baby shower for Sue Jacobs, July 17.

Mrs. Peters, black with beaded item, Novarese tunic dress came in.

Sue Ekahn came by with info on her couture lingerie. She will call in August.

Kathy from Mona office to purchase Filofax and gift certificate for Chris.

A special-order green dress with lace came in, and Mr. Beene is interested in knowing how it fits. Call him.

Sylvia Weinstock called about having a drink and Mother’s birthday cake: lilies of the valleys and violets? When was the actual date in June?

Candice Bergen and Bill Hargate for Murphy Brown tomorrow.

Rita Ryack called, may bring Lauren Bacall next week.

How safe I felt behind my desk contemplating a day of serving others! Until that moment I hadn’t fully realized how much the office was my stronghold.

I looked out my window at the Callery pear trees that were always the first to bloom. Their showy white flowers burst like fluffy clouds around the fountain. From that view I tracked every leaf and flower that blossomed to tell me how the seasons were progressing. Since I was very small, I have grown everything I possibly could, collecting carrot tops, grapefruit seeds, and anything else for my most precious possession: a greenhouse the size of a dollhouse.

Yet ironically, with the love I have for everything green and flowering, I had always fought anxiety and depression with spring’s arrival. I preferred the dark of winter, when my home is more welcoming. Summer’s very long days are too unplanned. Vacationing is not my strong suit.

After six weeks away from the office, where time is structured and I’m at my highest comfort level, I understood that for me this was truly my “safe harbor.” All those years in the outside world, I was afraid to take a step. In this very insular place, I confronted so many people’s insecurities and sadnesses that it forced me to become more articulate and resilient.

During my sessions with Philip, I had a recurring dream that I was standing at my office window holding a gun. A rifle, no less! I had never held a gun in my life. This went on for years, and Philip and I sifted through many involved interpretations. Why was I standing at this window? Why was the gun pointed out? We never resolved what it meant. I’m not a big believer in giving every symbol a neat meaning. It’s just like dressing: I turn away from anything that’s overdone. I did, however, wonder what exactly I was protecting.

CHAPTER

* * *

* * *

Nine

The phone rang early in the morning on January 2. It was Jim’s daughter.

“Betty, are you ready to hear this? My dad died today.”

No, I wasn’t ready. Who is ever ready? When Sonny and I were together, I used to lie awake at night worrying that I would get this call about him. Little did I know that bad news comes early in the morning.

While death is always a shock to the system, Jim’s was particularly so. Just the day before, he had driven me home from the Bridgehampton home of my former Chester Weinberg colleague and now dear friend Maria, where we had rung in 2008. Celebrating the New Year with Maria and her husband, Bill, had become a tradition for Jim and me. We always arrived the day before their annual New Year’s Eve black-tie celebration, so that the boys could watch football, go to the grocery store to pick up last-minute forgottens, and nap. Meanwhile Maria and I chopped, sorted, sautéed, and bickered about the placement of the flowers. (When she cooks and entertains, I am definitely the sous-maid.) After guests arrived at nine o’clock, we feasted on a traditional Italian New Year’s menu, including homemade lasagna, torrone, champagne, and cotechino e lenticchie. The idea with the last dish of sausage and lentils is that the more lentils you eat, the better luck you’ll have. Jim had seconds that night.

It was a good swift death, which was wonderful for Jim but awful for me. One day he was my male companion of twenty-nine years, the next he was gone. Jim loved me, but more so he tolerated me. I gave him a hard time up until the day he died. In Bridgehampton when Jim went up to take a nap, I nagged, “Why are you doing that?” I knew very well why he was taking a nap; his energy level was different from mine.

Despite all those years together, during which Jim put up with me and in turn I cherished him as my best friend and confidant, we never once talked of marriage. That’s because our relationship—healthy, mutual, strong—was never the love affair I’d had with the man I was married to. And Jim knew it.

There wasn’t the sexual attraction I had to Sonny or other men. However, something better came out of it. When I met Jim with his very soft way, I bent. I was ready for someone to take me over and teach me how to be a grown-up woman. Sonny had never trusted me with anything but a weekly allowance, and my mother and father had raised me in a world where you didn’t discuss money. Jim taught me how to address my checks to the IRS, found me Scott, a lovely local man who helped me build up some savings, and showed me how to discuss business matters with my superiors at the store—or at least to pick up a phone and try. (Scott is still my trusted adviser.)

My mother never quite understood the relationship. Not only was he not rich enough for me, but we weren’t from the same background. My daughter, on the other hand, always thanked him for being there for me.

Jim was a real, true friend who understood and accepted my craziness. In the spring when I spied bushes of lilacs or lilies of the valley, he pulled up the car and lowered himself behind the wheel so no one could see him while I picked and pulled to my heart’s content. Never enough. Often an angry owner would appear to scold me, and I would apologize, run to the car with my bounty, and drive off. Jim never begrudged me my thievery.

Before Jim’s funeral John and Kathy drove me to his apartment in New Jersey to pack up my things and some of the belongings we shared. There I found evidence of the last moments of his life—how he had made the bed, perked some coffee, and vacuumed. He knew when I came out two days later there would be an inspection. The only mar in his meticulousness and sign that he felt ill was the imprint of where he had laid his head on the plumped pillow.

Despite my grief I sanely collected the clothing he had adored. He wasn’t sophisticated, but he and his friends had dressed to the nines. If they had two coins to rub together, they managed to have the right tie, blazer, loafers, fedoras, the works—even argyle socks. He and his friends—especially Eddie, who looked like someone out of an English menswear ad—would dress just to have lunch in an unassuming restaurant in the sticks.

Although Jim always looked straight out of Brooks Brothers or Paul Stuart, he purchased pieces for his wardrobe from everywhere. He could go to the outlets in Flemington, New Jersey, and come back with the best. Before I met him, I had never been to an outlet store in my life. Yet I, too, learned how to shop there with taste. After Jim’s funeral I dispersed the treasured clothing among his friends: the beautiful neckties and Jim’s Borsalino to Eddie, the sweaters and socks to John and Bill.

Just as Jim and I didn’t discuss marriage, so Sonny—who never returned to the Park Avenue apartment again—and I didn’t once broach the subject of divorce. When my mind quieted down and I had established a career, I was still not able to put him on the back burner. Sonny was a burner for sure—but not really in the back. He didn’t support me, but I was still his wife. I was somebody’s wife and hoped never

to cut that thin, formal line between us.

Obviously Sonny didn’t either, or he would have said, “Betty, let’s get this over with.” I have no idea whether he wanted to maintain a connection, as I did, or if he simply didn’t want to remarry. The woman he was with, the very same one he went to live with after he left me, was content with the arrangement. Even as the effects of Parkinson’s disease began to ravage him, she was very good to him. Sonny and I both chose completely different human beings the second time around.

I saw my husband at various occasions throughout the years, such as John’s wedding to Nancy in 1987, when he and Jim met for the first time and Sonny hideously asked, “What kind of car do you drive?” (Jim, in full control, said blandly, “A hatchback.”) Sonny, already in his cups, didn’t look like Sonny, at least not the Sonny I had known. From a very handsome human being, he had become a bloated and blown-up man who was obviously doing bad things to himself.

Despite that, and despite the fact that I never forgave him for not standing up for me with his family, I loved him until that day in 2004 when John called me at Jim’s apartment in New Jersey to say, “Dad’s passed away.” Sitting on the little couch next to Jim, where we had been watching television when the phone rang, I thought of how Sonny had suffered through illness in a way that no one should suffer. In his very last moment of tenderness toward me, he acknowledged what I had accomplished at work. “I always knew you would be something,” he said. My husband was not a bad person—weak, but not bad.

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist