- Home

- Betty Halbreich

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist Page 20

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist Read online

Page 20

His passing cut the thread that neither of us could, and I wept at the finality. Suddenly anger and disappointment were hopeful feelings when compared to the nothingness left by death. Jim did not deny me my sorrow, for he understood the grief I felt as Sonny and all my complicated emotions toward him disappeared into a void.

Now the void had swallowed my Jim. How my life changed after he died so suddenly. When you lose a husband, you go back to many things: your first date, the sexual experience, children, building a life, and in my case the crumbling of a life—so many sad times as well as happy ones.

However, Jim left me intangible yet real things. Through his kindness and honesty, he influenced my inner strength. Losing Jim was like losing my best friend.

Until Jim met me, he had lived a very cost-conscious existence, with never much money left over for theater, restaurants, or any other of the plus things in life. The resources of my network served us as well as it did my clients and allowed for things Jim would never have done alone—namely, travel. One summer we rented a gorgeous stone farmhouse in Tuscany from a friend of Maria’s, where we closed the shutters every afternoon and kept out the heat. What fun it was to do all of Tuscany—the hill country, vineyards, small restaurants where we sat outside and ate food fresh from the earth that day—using a Chianti map!

People I knew through the store assumed I would hunker down at some tony hotel when I traveled. On the contrary. Jim and I preferred housekeeping, be it in Italy, Ireland, London, or New Jersey. In Tuscany we ate one meal a day out and went home for either lunch or dinner. Once, while shopping for fruit early in our stay, I was picking out plums when the vendor became agitated. In Italian (“Non toccare il frutto”) he demanded I put down my plums and proceeded to hand them to me one by one. In an Italian supermarket, three women giggled at me to my face while I went through the checkout counter. I finally realized why: I had my T-shirt with a logo inside out. Why they thought that hysterical still boggles my mind.

We rented an apartment in London, not long after my cancer treatment, in a building where my cousin’s British ex-wife lived. We were thrilled, because it had a lovely garden and was located in Camden Town, which was very funky at the time. But everyone, and I mean everyone, was very unsociable to us. The only person who ever greeted us with a hello was the milkman, and we didn’t drink milk. Jim and I rose above it and had a great time all the same, sitting in the beautiful parks, smelling the roses, and being real tourists.

Our best travels, though, by far were the magnificent summers we spent in Ireland. I had a young assistant whose parents rented us a house in Durrus, a village in County Cork known for its wonderful locally produced food (which meant more farm stands for poor Jim). We rented a car and for nearly a month traveled the country’s breathtakingly harsh coastlines, verdant hills, and towns with ruined castles and little houses with thatched roofs covered in flowers. The sweet peas, in abundance during our trip, were completely unlike their scrawny American counterparts. Oh, the colors!

Jim kidded me about my eating smoked salmon in Ireland; I literally could not get enough of it. Every pub we lunched in had the exact same menu: egg, egg salad, ham, ham salad, salmon. It became our theme song, and I always chose the salmon. We gorged ourselves on egg yolks the color of oranges, thick slabs of bacon, butter and clotted cream the likes of which I had never tasted, and dark, nutty Irish soda bread one could eat by the loaf. Whatever cuisine we chose for our evening meal came with three kinds of potatoes. Even Italian.

Jim’s Irish humor blossomed in pubs full of blarney and all through the Auld Sod. The locals milked a brew all day while they talked and talked. By the time the bartender pulled them a second beer, you could be in another country. When he went for the local newspaper (he was addicted), he would be gone for an hour or so, talking to the locals about fishing. He came back with promising tales of what they were going to catch and bring us. Not one fish did I see.

The place felt so familiar and comforting to me, a nice Jewish girl from Chicago, as well. I was back with the people who had raised me, after all. We talked about buying a home there.

On our last trip, I tried to connect with one of John and Kathy’s nursemaids, Rita, who had left us when the children were early school age to return to marry. When John was seventeen, he took himself to Ireland, found Rita and her family struggling to make ends meet on their farm, slept in their barn with the animals, and loved every moment. Rita, however, passed away the year before my trip and, much to my sadness, left behind four children. When Jim and I arrived to meet them at the local hotel for tea, they were already waiting for us in their church best with their father. They had brought along a framed black-and-white photograph of their mother, in her white uniform and coat, with John and Kathy, both in their English Sunday coats, taken long ago atop the Statue of Liberty.

When you age, death seems to creep into early morning phone calls, the hands of small children, and, in my case, a leather-bound datebook’s growing number of names and numbers of people who no longer exist. Although the list is long, I never scratch anyone out of my directory book in the office. You do not delete names because a person is gone. The loss is painful enough after years of caring for them. When I see their names in my pages, I think fond thoughts of silly things we did, of lost packages, hems too short, suits that made them feel unconquerable.

Doris: How I had admired her patrician stance since we summered at the same beach club when I first arrived in New York. Everyone did. In all her years, I never saw the woman—who raised three sons, all very successful in business, and lived through the demise of her husband—lose her strength, dignity, and graciousness. She had a wonderful woman, Elaine, who took care of her needs when she became older and frailer. Together they laughed, went to movies, ate meals. After a bad hip operation, Doris carried a silver-headed cane, which she despised, flung in all corners of the dressing room, and often used to swat me with during fittings.

Mrs. W: A most forbidding woman from Virginia, who led a very active life and bought tailored clothes of the season like she was a dictator. Cristina and I were called up to the president’s office to defend ourselves against some complaint she had against us that I no longer remember. Not much later she fell on the marble first floor, broke a hip, sued the store, and wouldn’t let it go. Then the president saw the real Mrs. W, and we were vindicated. (Twenty years later a new young customer came to me with the same last name. I asked her if she was related, and, by God, it turned out that Mrs. W, whom she called “a monster,” was her husband’s step-relative.)

Estelle: A dear personal friend of mine became a client because her husband, who picked out her clothes, fell ill but still wanted her to “look pretty.” She switched her dependency from him to me; I had known her from my previous life and worked hard at keeping her looking just as her husband, who had great taste, would have liked. She bought very lovely clothes until she, too, became ill.

When her children asked me to go through her closets after she died, I revisited all the clothes I’d introduced her to. Only now, as they went from objects of desire to pieces of nostalgia, they took on a new and painful meaning. The Bill Blass dresses she’d once accessorized looked forgotten; the Givenchy pantsuits that had framed her elegantly seemed as important as a dishrag. Her girls asked me if there was anything I wanted from the vast amount of clothing. Yes, a Geoffrey Beene navy-and-white dress, which I still wear. Even more than Mr. Beene’s remarkable construction, it is the human connection that I treasure.

My work with clients often does not stop at the grave. Having watched many children grow up in my fitting room, I always make myself useful to them in any way I can when a parent dies. For dear clients I have been known to help in the disposing of extensive closets, as I did with Estelle. I write condolence cards with insights they might not have into their parents. (“Your mother always took risks in fashion,” I wrote to the daughter of one extremely reserved and b

ookish woman I draped in scarves, camel coats, flannels, and tweeds.) I also dress children for the most difficult day they will ever pass.

My client Mona fought up to the very end, but eventually cancer won. When her death was imminent, a good friend of hers called to say that her daughter, Gila, was coming to New York with her young children, having grabbed the first flight from her home in Boulder, Colorado. Would I get something for her to wear for the funeral and the days to follow?

Sifting through the racks, from the outside I looked like anyone else in the store. On the inside, though, I was stricken. I had known Gila—an accomplished psychiatrist and mother—since she was twelve. While I looked for a simple dress and a coat to go over it, I couldn’t indulge my sorrow. I turned away from black, for Mona would not have approved. Too, too sad. Instead I worked around navy skirts and tops. The coat served a great purpose, as it not only completed the outfit but also made it reserved rather than heavy. For receiving at home, I did pants and easy sweaters, throwing in a bit of soft color in tops for cheer. Gila did not come in; she was grief-stricken—as was her brother, Ari—and had two small children. I organized and labeled the pieces of the wardrobe so that she could choose from her apartment, where I had everything sent. I watched her speak from the podium in the temple, wearing what I had chosen. Amid all the sorrow, I was happy that a bit of me was up there with her.

A couple of months later, I received a call from Gila—she was coming to New York for a family wedding and again needed help. I was so pleased, even though without Mona the visit would be bittersweet. But I was ready to play surrogate and relive the fun experiences that belonged to the past, down to serving the tea sandwiches her mother had adored.

Gila and I had the most delightful time, laughing and keeping up a running dialogue under the subject line of “What would Mona say?” She was adorable in everything. During the fitting I watched her exorcise a lot of grief. The clothes she took were bright, and much more current (Mona would approve!) than her usual. Her mother was included in every cucumber-and-butter sandwich, every pair of jeans, and every joke—so much so that we actually felt her laugh in that fitting room.

I was happy with Gila’s visit. Coming to the store was theater, an adventure, a way not to be sad. Although her grief was still there, she put it on the shelf. What replaced it was a woman, a very adult person, who could look in a mirror.

I understood her loss intimately, because with the passing of my own mother I knew what it meant to mourn the death of a vibrant, fun woman adored by many. While she had always been a standout from the crowd, in the years between my father’s death and hers, Mother really came into her own.

Once she no longer had a husband to tend to, Carol Stoll started a whole new life that centered around her beloved Oak Street Book Shop. Not long after my father died, she went to work at the bookstore, which she quickly took over and transformed into a Chicago institution during her twenty-three-year tenure.

Mother had always loved books. There are photos of her as a child carrying a book, and she was always a huge reader—as were my grandmother, my daughter, and I. But what she had going for her more than her passion for the written word was her ability to sell. Mother was what they call a natural-born saleswoman.

Her talent for retail began with the impeccable taste she had in everything from table linens to literature. While my father was still alive, Mother built a wonderful gift shop for the Weiss Memorial Hospital in Chicago with her innate merchandising ability. Unlike the other ladies who devoted their time when they were not wintering in Florida or playing golf at the club during the summer, she and my father didn’t go anywhere or play anything. So Mother ended up with a full-time, completely unpaid job at the gift shop, and she loved every minute. Under her reign this was a place to buy not tacky Mylar balloons or stuffed animals with cloying sayings but beautiful handbags and lingerie that all the doctors purchased for their wives.

As owner of a bookstore, Mother swiftly turned it into a lovely clubhouse whose location bore the imprint of her fine judgment. She understood Oak Street’s appeal way before Joan Weinstein opened up her famed fashion boutique, Ultimo, down the block. The street that went from spottily chic to a premiere shopping destination known for its luxurious local boutiques was made up of nondescript little stores on the lower level of brownstones where young people lived inexpensively when the bookstore moved there. Across the street there appeared to be a bunch of old row houses. But behind the façade was an elegant mansion owned by Colonel Leon Mandel, who also owned Mandel Brothers, the Chicago department store where my father was president. The town house he shared with his beautiful Cuban-born wife, Carola, boasted a swimming pool on the main floor. It was a very secret sort of thing, but mother, who knew everyone and everything in Chicago, went all the way back to her school days with Leon.

Mother gentrified her brownstone by planting window boxes on the iron fencing in the eight steps up to the bookstore’s landing. Every spring her Martha Washington geraniums and white petunias brought irresistible charm to her little corner at 54 East Oak Street. If passersby touched them, which they often did, she poked her head out the window and yelled. That was her garden.

From that window where she sat seven days a week, she had a view of everyone on the street—and they of her. From behind her hundred-year-old cash register, which terrified me, she knocked on the window when people went by to urge them to come in. If she’d had a hook, she would have used it to haul in customers.

Her desk was unbelievably cluttered with clippings, receipts, always a potted plant of some kind, and an ashtray full of cigarette butts. She lived on black coffee and cigarettes until she quit smoking. Behind her was a board where she kept photos, messages, and coffee mugs engraved with the names of all her special customers: Norman, Gardie, Irving, David, Gene.

In her bookshop she cultivated a whole coterie of successful men (never a woman in the bunch). It included Norman Wallace, who played piano in the Chicago supper clubs; businessman and supporter of the arts Irving Tick; film critic Gene Siskel; and playwright David Mamet. These members of Chicago’s intellectual elite debated with, confided in, and absolutely doted on my mother. Gardner Stern (Gardie), a married man with four sons who was the handsomest human being in the whole world, visited her every day after he retired.

Through a narrow room loaded with books—on either side and down the middle, stacked as high as the ceiling—past a small room housing works of drama where students from Northwestern sat reading for hours, there was a tiny single-burner kitchen where coffee brewed all day long. She served so much Hills Brothers coffee and Sara Lee coffee cake that I used to say to her, “Mother, your profits are all in the refreshments.”

People called the Oak Street Book Shop an old-fashioned store, but Mother ran it exactly as she lived: with graciousness and personality. (At the luncheonette around the corner where she had breakfast every morning, which was, of course, coffee and coffee cake, they always put out a real place mat and a cloth napkin when she arrived; Mother did not approve of paper napkins.) She was equally good at teaching the rudiments of living well. That was a part of her important relationship with the renowned photographer Victor Skrebneski and designer Bruce Gregga. (They also had personalized mugs.) My mother met them when they weren’t much more than young hippie guys from mundane childhoods in North Chicago, the industrial suburb that was home to many Eastern European immigrants. She was Victor’s intellectual and aesthetic muse as he rose to fame snapping portraits of the likes of Andy Warhol and Bette Davis and discovering Cindy Crawford. Bruce, who got his start as a stylist and set designer for Victor, became popular among some of the influential and hip new young entrepreneurs.

In return, Victor and Bruce entertained and kept Mother safe as she started this new life of work, dinners, friends, and travels without my father. She became more flamboyant in all things, even her fashion. She wore feathers, a haircut with bangs, and

sequined evening dresses. (After a night at some grand party, she couldn’t unzip her sequined gown, so she slept in it until the elevator man arrived at seven o’clock the next morning.)

Mother, who dressed beautifully from the time I remember, loved clothes, hats, and femininity. She looked like a lighter, prettier version of Diana Vreeland. Her taste was her own—no one could sell anything to my mother because it was new or the thing to wear. She bought Ungaro’s print dresses and coats and adored feather boas. No matter what the circumstances, she was up-to-date, and with very little effort. Whether a new dress or a pin in the right place, she had more flair than anyone else in her group of friends. They worked at it, and she was born with innovative taste. For that reason her friends always asked her to go shopping with them, where Mother employed a secret code for delivering verdicts in front of sales staff: “Thirty-four” for “Good” and “Thirty-six” for “Awful, take it off.” I have often wondered if any of the salespersons caught on to their trick. Shopping was a true activity.

Carol Stoll moved with the times. She took herself down the street to Ultimo. In the appropriately avant-garde interior of tented batik cotton, red-lacquered Chinese furniture, and a chandelier of stag horns and a ship’s figurehead (all designed by Bruce Gregga; Chicago is quite a tight society), Joan introduced my mother to the new, younger, trendy way of dressing. Still a size 6-8, Mother looked good in the new European designers like Jean Muir and Sonia Rykiel. Victor favored her in an Emilio Pucci black dress with a shocking pink geometric print. She went all out to make herself very chic, and she succeeded.

The one thing that did not suit my mother was getting old—does it anyone? Like me she didn’t look in the mirror a great deal, but she had a certain vanity about her. She never told anyone her age—not even me. I was always quite unsure of it, until her death, because it never mattered. That is, until she had to close her bookstore after the rent tripled to an untenable sixty-five hundred dollars a month, and she seemed to grow old overnight. She was like a balloon with the air leaking out.

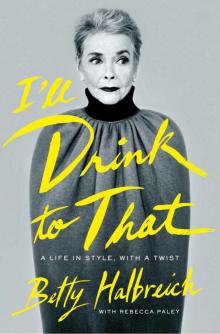

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist

I'll Drink to That: A Life in Style, with a Twist